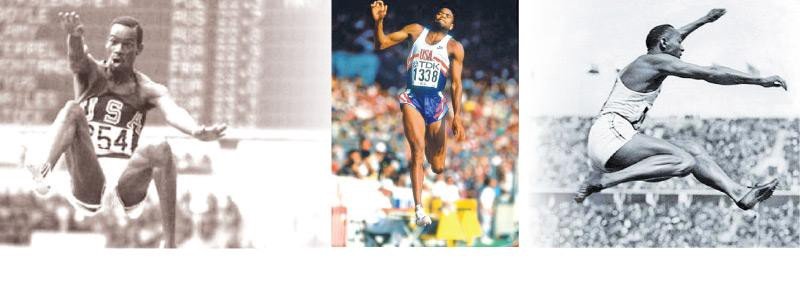

A Puzzling Look At Why The Men's Long Jump World Record Has Not Been Broken in 31 Years

What factors have contributed to this decades long drought?

Jamie Mah @grahammah

On the heels of this past August’s Track and Field World Championships in Eugene, Oregon, an event I sorely wish I’d been able to attend, my mind cannot stop circling around a puzzling event, the men’s Long Jump. As someone who competed in Track and Field for many years growing up, specifically in said Long Jump, my lens regarding this event is often heightened to those who compete and win, but also how the event has evolved, in this case: Why has no one broken Mike Powell’s world record in 31 years?

If we’re to dig a little deeper, you could ask this question in relation to the men’s and women’s High Jump where those records have stood for an even longer period of 34 years.

When thinking of Track and Field most gravitate to its marquee spectacle, the 100m dash, a race of pure power and bliss. Nine men or women stampeding down a beautiful track with 60,000 people screaming enchantingly. It is athletic theater of the highest regard and I love it!

Humans are found to be in awe the most when we witness the profound. Stephen Curry of the Golden State Warriors is a shining example of this archetype. His frame lends him to the land of mere mortals as he stands a modest (for NBA types) 6'3". Relation brings with it a singular comprehension. A deeper understanding. He’s tall, but not too tall we average folk can’t relate. Factor this ethos with the coupling of his rare gift, that of unparalleled shooting, and there have you a player who stands taller(!) above everyone else in his field. Hence why we adore him and why he continues to win. His excellence is something we’ve never seen before.

For Track and Field of recent lore, Usain Bolt was its superhero. A man of high stature (he’s 6'5") whose cadence was one we’d never witnessed before. His excel phase was one for the ages as he so often cruised past his field with a mere caution in the wind. If you’re looking for confirmation of this, just ask fellow Canadian track hero, Andre Degrasse.

Never had we seen a sprinter of his skill level. Not only did he smash the world record but he took it to depths we might not yet see for sometime. Or so we think?

When considering world records in Track and Field it is best to think of things as a set of progressions. All sports improve over time. Players learn from those in the past. Diet, training and technology add elements for growth. Couple these with our insatiable human desire to conquer new challenges and there you have a recipe for advancement. Most records don’t stand for too long. It’s why LeBron James is a better player than Oscar Robertson who played in the 1960s and 70s. He’s had advantages Oscar never had.

Therefore with respect to the men’s 100m, let’s have a look at how this event’s world records have progressed since 1912.

**The first record in the 100 metres for men was recognised by the International Amateur Athletics Federation, now known as World Athletics, in 1912. As of 21 June 2011, the IAAF had ratified 67 records in the event, not including rescinded records.

As you can see, it’s downward trajectory has fallen along a nice steady slope, well, that is until the very end where you can see Bolt’s acceleration of things.

Now here’s the men’s long Jump progression.

If you’re wondering why I’ve presented a more colourful and highlighted example of the men’s long jump versus the men’s 100m it’s because of the rarity of the latter. Three men have essentially held on to the record for over 20+ years each, with Powell’s stretch being by far the longest. In the longstanding comparison of the turtle versus the hare, it’s easy to see which event the other is. In sports this should not exist. Once again, the dilemma I’m wondering:

Why have the jumps events stopped improving?

I have a few theories I’d like to examine and a few I’m going to showcase from other sources, who, like me, have also bandied about this query.

The Long Jump no longer gets the best athletes.

Six of the top seven men on the all-time long jump list are American, but only one of those athletes, Dwight Phillips, has set his PR since the turn of the century. One theory is that the freak athletes like Beamon and Powell are no longer finding their way to the long jump.

“The best athletes are playing the big (team) sports,” says Nic Petersen, the renowned jumps coach at the University of Florida. “They’re playing football, they’re playing basketball. So we’re not necessarily getting the same level of talent that maybe was going on in the ’90s.”

Powell, who idolized Carl Lewis as a teenager in the early 1980s, agrees.

“When Carl was jumping, Carl made the long jump glamorous and so we had a lot of athletes going into the long jump,” Powell says.

But Powell goes further: he believes that even within track & field, the long jump is not getting the top athletes. In his prime, Lewis wasn’t just the world’s greatest long jumper, but the greatest sprinter too, winning back-to-back Olympic 100-meter titles in 1984 and 1988. Today, very few professional athletes double up in the sprints and the long jump, and Powell believes that many of the athletes with the sprint speed to become a world-class long jumper become sprinters instead, where there is more money and fame available than in the jumps.

“Since [Carl and I] stopped jumping, it’s really fallen down compared to other events, 100 meters, 1500, pole vault, stuff like that,” Powell says. “We’re a C-level event now. So a lot of athletes don’t even go and try and do it. I mean [Usain] Bolt, that was an obvious thing for Bolt to do and he didn’t feel the desire to go and try to do it.”

Lewis, a four-time Olympic long jump champion, doesn’t totally buy this argument — “I just think it’s a cop-out [to say the talent has gone to other sports]” — but Lewis did admit that it’s extremely tough to balance a career as a jumper and a sprinter. When Lewis decided to chase four golds at the 1984 Olympics — in the 100, 200, 4×100, and long jump — he felt that his long jump suffered because he was not able to devote as much energy to it as a pure jumper would have (it didn’t suffer thatmuch; he still won the gold in Los Angeles).

“A lot of great athletes in track & field stop long jumping because it’s too hard,” Lewis says. “I don’t think it’s other sports; I just think the event’s too hard.”

How I land on this argument is kinda in the middle with how Powell and Lewis feel. I do agree that top level sprinters such at Bolt have walked away having spent all of their focus on the glamour sprinting events, which in theory, was probably the correct call. Part of me believes that to excel at any particular event in the 21st century a singular focus is what one should covet. I say this not to take away from the achievements of men such as Lewis who excelled at both, but more so in saying that the level of competition today is much more gruesome than it ever has been in the past, especially with the Diamond league events and all the money that’s up for grabs there.

There’s too much at stake compared to days of the past. The NBA is in throes of this issue currently with players resting way more than they should, in part because they’re making so much more money than they ever have. When money starts to devalue the degree at which athletes try, everything suffers. But this is a topic for another day and not entirely in line with Track and Field, but it’s not far off either.

This way of thinking, however, speaks to how sports in general have evolved with money on the line. There’s more to be had than ever before and as such, it has forced athletes to choose one thing over another. As much as Bolt had to gain personally as an all around athlete if he’d competed and won in the long jump, the amount of money he was able to make while focusing on the 100m and 200m over his career cannot be underscored. He’s considered the greatest track and field athlete of all time (a mark Lewis might have something to say about), which gives him little to lament regarding how his career unfolded. Yet, it is hard to wonder how he might have fared in the Long Jump had he given it a go.

Nevertheless, not all sprinters are so lucky, thus I do agree with Powell’s assessment, but I also see Lewis’ perspective. It’s really hard to do both, sprinting and jumping. It’s why even he stopped doing both late in his career. Some have the energy and desire but many don’t. But again, I also believe in cycles and the power of what people see. If one day a young 19 year old starts breaking records in the long jump while giving it some panache, similar to how Curry has emboldened young kids into shooting long range three pointers, a change in perspective could be had. But alas, that might be awhile before it happens. I mean it has been 31 years already and there’s still a big gap between what’s happening in the pit today versus what Powell and Lewis were performing that fateful night in Tokyo in 1991.

2. Are we overlooking the doping era?

It’s easy to forget that not too long ago the entire sport of track and field found itself under intense scrutiny regarding steroids and doping due to the Ben Johnson scandal of 88'. The then 100m world record holder and fellow Canadian tore down the fabric of sprinting integrity with his positive test after the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics. It not only ruined his career but it painted a horrible stain on that event and track as a whole for a very long time. With a revisionist lens, I firmly believe many more cheaters got away with their crime’s once Ben took over everyone’s focus.

From Forbes: (emphasis mine)

No matter how strong their performances, it is unlikely that anyone will come close to Florence Griffith-Joyner’s time of 10.49, set in the 1988 U.S. Olympic Trials.

Flo Jo, as she was nicknamed, became a household name leading up to and during the 1988 Summer Games in Seoul South Korea. She boasted Usain Bolt, movie star levels of recognition. Over that summer, she set the 100 meter record (10.49) along with the second and third best times ever and the 200 meter record (21.34) along with the second best time ever. In both cases, she obliterated the previous marks, lowering the 100m record by 0.27 seconds and the 200m record by 0.37 seconds — unprecedented reductions.

The questions will always linger, especially given the cloud of track and field at the time along with the magnitude of her improvements over the summer, beyond just the Trials. Her best time in the 100 meters prior to 1988 was relatively modest 10.96, currently the 509th best time ever. In the 200, her best before 1988 had been 21.96, now the 75th best time ever.

In spite of nearly 30 years passing, female sprinters since Flo Jo have not been able to come near her mark. Carmelita Jeter holds the 4th and 6th best times ever in the 100 meters, but her times stand 0.15 seconds above Flo Jo’s as are the the times set by Shelley Fraser-Pryce in winning the last two gold medals in the event. In the 100 meters, 0.15 seconds is a big gap. The same holds for the 0.28 second gap between Flo Jo’s record and the next best person in the 200 meters.

t’s not just Flo-Jo standing in the way of female sprinters finding a place in the record books. The 400m record was set in 1985 by an East German runner with almost all the top times held by Soviet-bloc runners from that era. The best runners from outside the Soviet bloc are more than a half-second slower and these are from 1996. The best time since the 1990s is held by Sonya Richards Ross at more than a second behind. The same Soviet-bloc story appears in the 800 meters, which is a transition between sprints and middle distance, albeit to a lesser extent. While individual runners may have escaped detection, the state-sponsored programs to enhance athlete performance in these Soviet-bloc nations is well known.

So, whether Flo Jo’s marks were due to a brilliant summer or other influences, why have they and the Soviet-Bloc records stood so long? After all, Ben Johnson’s time at the 1988 Olympics would now rank at or below that of seven other runners as only the 34th best time ever. Where steroids have been employed, they improve the running performances of men and women, but the relative impact appears even higher for women.

The indication from these stories and interviews is that, while it is present, the cheating isn’t nearly as blatant or constant as in the 1970s or 1980s. To avoid detection, the dosages are kept at relatively low levels and may be only intermittently used.

Apologies for the length here, but I wanted to highlight the importance of what Flo Jo achieved in 1988. Like several others from that era, her improvements heed suspicion. Her numbers are staggering to this day and are only now beginning to come under threat with several women driving her gap down over the last two years. It has taken this long and she’s still on top. This is in the sprinting world, where world records fall like prom dresses.

Something doesn’t add up.

And this doesn’t even factor in the little nugget within this excerpt about the women’s 400m world record from 1985!!!

I went into this column with a myopic lens regarding the men’s Long Jump and have thus emerged so far with a greater understanding of the peculiarities towards select world records for other events. The fact that so many records sit within this narrow window from 1985–1993 leaves me to wonder, as you should also, whether a cloud of doping larger than just one man (Ben Johnson) was at play?

I suspect that his casualty of fire at the 1988 Olympic games might have been all that was needed to slowly rid the sport of the excesses of heaving doping. As the Forbes piece alludes to at the end, cheating most certainly still exists (re: Marion Jones, Justin Gatlin to name two recent notables), whether at this scale, we might never know, but it goes without saying, with several records still at play here that Ben Johnson was almost certainly not the only cheater from that era. He was just only one to get caught.

Nevertheless, ultimately these two main points bring me back to the men’s Long Jump and where it stands today. Currently the top performance this year has come from Greek jumper, Miltiadis Tentoglou, who jumped a very impressive 8.52m on August 16th. After him most of his fellow competitors fall in line in the 8.20–8.36m range, with one jumping 8.45m. These numbers are consistent with most seasons since 1991. In fact, only four men have jumped longer than 8.70m since Powell’s record setting night, with the longest among them being 8.74m.

Curiously though, despite big leaps in training, technology and diet, the efforts of everyone competing since 1991 still haven’t lifted the sport to what it once was or possibly could be. One would think the 9m mark would have been broken by now no. It’s been 31 years! No progress whatsoever?

Similar to the steroid era in baseball twenty odd years ago, the sport of Track and Field is still haunted by the era of the 1980s. It may rarely be brought up, but the stink still lingers. Coupled with the continued curiosity of the sprints in favour of the jumps and other less notable events, many of these jumping records might stand for years to come. Sadly, like most things in life, this dilemma begins and ends with money. Shot Put will never command the attention of the casual viewer. Money flows where interest lies. Long Jump for all its athletic splendour is invariably a B level event in Track and Field. It will never command the attention or money needed to garner the best athletes to truly take it to new heights. By chance it may happen one day, but that will be more an example of luck rather than expectation. A paradox of sorts if I’m to say so myself. One I’m content in accepting, even if one day I’d love to see another great jumper(s) take over the event I care so deeply about.

Who knows, stranger things may happen. Only time will tell.