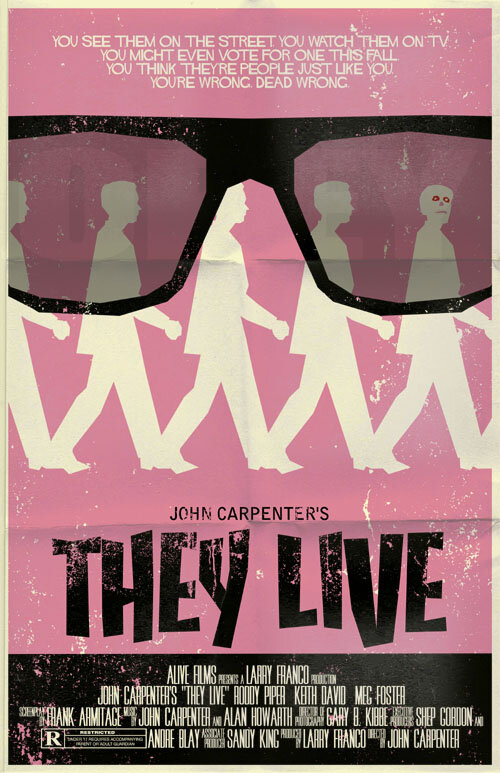

Separating The Good From The What The Hell In John Carpenter's They Live

The 1988 cult satire’s skewering anti-capitalist take is as relevant as ever, but also there’s just some weird choices in this movie

Tristan Young @talltristan

The ever cavernous and obnoxiously sprawling gap between capitalism’s chosen winners and everyone else grows larger and more incomprehensible every year. The gaping maw that separates an increasingly concentrated caste of elite and their sycophantic surrogates from the rest of us is vast enough to be subject to a broad spectrum of analysis and interrogation. Nearly every medium from traditional literature to video games have operated along this spectrum, carving out a thematic stake- or rather aesthetic illustration- along it. Those illustrations render with the intent to clarify and illuminate the moral outrages of late stage capitalism, in direct confrontation with the institutional structures that would have these systems hide in an opaque black hole, beyond the gaze of the public’s awakening scrutiny. As no iteration of film, novel, music, etc. has fully cracked the code on how to truly do something about it, there is no wrong way to undertake this moral crusade. As such we have experienced projects that look at malignant capitalism as an ideological mutation, and done so with the precision of a surgeon’s scalpel, such as in The Big Short. Elsewhere D.C. punk band Priests, who viewed the occult marriage of avarice and politics as a pre determined arrangement of manifest corruption, tackle the subject with the blunt force trauma of a run away bull in their album Nothing Feels Natural. This is all vital stuff. Along this breadth of options to approach the topic, ranging from laser focus to a jackhammer, we also have They Live, which opted instead- of course- for the suplex.

They Live was envisioned by John Carpenter as his paranoid opus against the spectral and subliminal evils of capitalism, Reaganism, and the further prevision of an already morally onerous ‘American Dream’. Maybe it is? Maybe it’s B-movie schlock, whose cynical opprobrium is obscured by it’s hackneyed ludicrousness. Even saying it’s somewhere in between would be construed as a misreading of They Live by many. It’s a movie who’s central idea is orbited by a constellation of smaller, peripheral ones, until they blot out the central vision meant to hold everything in place by the gravity of it’s rhetoric. When the interstitial fibres of those ideas prove too unruly to be grounded by its core thematics the movie spirals out of control. From there it is repeatedly destabilized by it’s own bizarre excesses masquerading as crucial exigencies.

Still, They Live is pretty fun. Furthermore as the laughably satirical- well, satire, of 80s and 90s hypothetical dystopias become ominously reflective of our current shit sandwich of a year, it’s worth revisiting the film and examining what worked and what didn’t. What moments reveal an edifying social commentary and which ones amount to little more than incoherent ramblings? Do the monsters hold up? Did Roddy Piper really say that line? Who or what is Roddy Piper? Put on your best (worst?) pair of sunglasses and grab some bubble gum, let’s do this.

WHAT WORKED

CASTING RODDY PIPER

Unbelievably, yes, he works out well in this movie. The roll of main character Nada, who is never actually referred to by name in this film (only listed as such in the credits), was originally going to go to long time Carpenter collaborator Kurt Russell. However, having cast Russell in a leading roll in four of his films already, Carpenter had a change of heart and decided to switch it up. Many better known actors were considered, but ultimately it was Carpenter’s life long love of pro wrestling that guided his decisions. Carpenter offered the role to star wrestler of at least middling fame, Rowdy Roddy Piper. Piper had no career in film to speak of but was excited by the opportunity. Vince McMahon, head of the WWF (as it was known at the time) reportedly didn’t want Piper doing the film, weary of his wrestlers finding revenue streams and career options that didn’t directly come from his graces. Piper, being fed up with McMahon’s anal-retentive tyranny quit the WWF to do the film. That his role in They Live is something of a sub textual middle finger to a historic asshole like McMahon makes his presence on screen all the more delightful.

Piper, either through his own natural cadence, or Carpenter’s surprisingly subtle definitions of the character, really does imbue Nada with a genuinely unique persona. As a drifter wandering though the ghettos of LA looking for any job and any place to stay, Nada clearly has been chewed up and spit out by the economic grinder that serves commerce at the expense of human dignity. And yet Nada is oddly unaffected by his derelict lot in life. Rather he still believes with earnestness that lands somewhere between sanguine naivety and refreshing confidence that if he works hard and keeps his head down he can still make it work. While Nada has a clearly more observational sensibility to him than those he shares much of the first half of the film with, he is more bemused by the delusional hijinks of the burgeoning resistance he finds himself embroiled in. While so many of his new co workers and friends operate in a state of perpetual agitation while their responses to very real grievances are unfocused (just as a shadowy, oppressive ruling class would want it), Nada seems more aware of the bigger picture and the perspective of his place within it; even before he finds the magic sunglasses.

WHILE WE ARE AT IT, CASTING KEITH DAVID

Having somewhat mastered the depiction of contrasting personalities forced into a pressure cooker situation to act as foils in The Thing, Carpenter was wise to bring back the ornery passion of Keith David. David first worked with Carpenter on The Thing and Carpenter was so impressed with his work, he wrote a role specifically for him in They Live. As Frank, David depicts an individual hyper stressed and mentally taxed by the callous indifference of a market based economy that had left him and countless others behind. He doesn’t want any trouble, he wants to save money for his family; he really doesn’t want any trouble. His frustrations borne from playing by the rules in a system that rewards cheating are tangible, worn on his face, vibrating within the oscillations in his voice. He’s had it but doesn’t know how to do anything other than keep trying. He has accrued a considerable amount of wisdom from his time on the earth but that knowledge has only accentuated and highlighted his misfortunes. To him, learning any more, traveling further than he wants down the path of radicalization is a ruinous choice. Franks understands the perilous hazards that come with not being able to unsee, whereas Nada has a flippant and capricious attitude right up until he realizes he’s in too deep. No wonder these two become friends/ almost kill each other.

THE ALIENS

Far from being monstrous abstractions with frighteningly asymmetrical designs that often bisect creature horror and zombie horror, the malevolent alien overloads from Andromeda are unnervingly streamlined. The paraphrased marketing tag lines of them looking just like us isn’t far off as their actual body shape and outline is the same as ours. However, taking facial designs inspired by what looks like the earliest version of the fly and integrating predatory teeth and oddly bedazzled eyes, the look of the creatures is an excellent cross between demonic idolatry and far out sci-fi. They don’t look ‘hi tech’ as Carpenter wanted to move away from that. Instead we see walking corpses, corrupted avatars of ourselves meant to represent our twisted humanity. That they talk with completely normal voices adds a layer of benign obfuscation to their visage which make there covert integration into society all the more surreal and sinister. The gilded twinkle in their jewelled eyes effectively demonizes the pursuit of wealth in literal but also efficiently economic terms. That could either be interpreted as yet another invective towards capitalism, or subtly faint praise of market derived innovation. Seeing the alien ghouls in color for the first time right at the end of the film, as they could previously only be observed through the black and white lens of the signal descrambling sunglasses, is even more jarring. The maroon mixtures of blue and purple tendons, drained of any blood- of any heart- conveys something not so much heretical, but artificial. If society and culture has been perniciously transformed from within to eject all matters of the soul in favour of commerce, the creatures that would facilitate this look similarly drained and embalmed. Fake vessels for a fake a life, as it were.

THE INCOME GAP AS AN EXESTENTIAL THREAT

Much of the film takes place in a make shift (but actually real) shantytown on the outskirts of downtown LA. The residents of the discarded diaspora are all depicted as one way or another formally middle class. These aren’t hardened criminals, they have jobs, and they volunteer at church. The only one with a real edge of misanthropy is Nada himself and he’s still a pretty good guy. The manufacturing sector in California took a big hit in the late 70s and early 80s, which Carpenter seems very cognizant of in creating the characters in this setting. Police choppers harass these people, lionized as the backbone of America. They are mocked by the parade of fashion models and luxury brands flagrantly on display on the one TV they can only sometimes get to work. When some in the group are suspected of dissension, it is treated as full on sedition and swat teams are called upon to destroy the town. Far from being put on a rhetorical pedestal by those that would exploit their image, they are hunted down by the very institutions that are supposed to protect them. In They Live, to be poor is to be suspicious, and then suspected. They don’t have the material means to meaningfully satiate the aliens’ thirst for commerce and consumption therefore they are wasted space at best, and a threat to be eliminated at worst. To be poor is to risk your life. When the police come the film takes on the tone of the a future hell scape ala Terminator (also LA!). Police officers hunt down children and pastors alike as the dead of night is pierced by oppressive and invasive floodlights. The unnatural lighting by way of dilapidated infrastructure creates the vibe of a war zone in a horror story. Nada desperately tries to save as many people as possible from the cops like they are being pursued by the T-800 itself. The movie is at it’s most genuinely threatening here, with the safety of peripheral characters at it’s least assured in moments like these, long before the reveal of the alien ghouls and their master plan.

RADICALIZATION

Just in general. As Reagan’s ‘Morning in America’ became to be understood as really just ‘Morning in white suburbs’, and the for the rest it was the war on drugs and crime (re: them), the idea of the American Dream seemed more and more out of reach and yet ominously inescapable. Less of a dream than a threat. By 1990 punk rock had taken several stabs at highlighting these, niche as it was in relative pop culture. Hollywood hits like the Running Man had undertones of Haves and Have Nots, but didn’t go far enough. They Live, regardless of its impact or lack thereof, advocates swinging for the fences and being as overt as possible in maligning a malignant system. Clumsy as the sunglasses metaphor/maguffin is, it directly confronts the dark core of economic nihilism as it hides in plain sight in effective and easy to understand visual language. It only seems simplistic and naïve insofar as the out of control income gap wasn’t nearly as expansive back then. Now all of the visual rhetoric seems fairly salient and succinct when contrasted against our present reality. Depicting the ills of our society not as the result of occasional bad actors and moral failings but as a system doing exactly what it was supposed to, designed by those who don’t have your best interests in mind is a necessary point, now more than ever. Defining those who would perpetrate this as so out of sorts with common decency that there is no negotiating or compromise to be had is a controversial argument to make as ever, dating back to the Black Panthers. And yet the mission statement of organizations like them grows more and more reasonable with each act of condoned institutional racism or corruption. Be it racial or economic injustice, the typical avenues for protest not only aren’t working, but also are being ever more infringed upon. They Live is of course a goofy satire, but the ‘goofy’ part remains firmly intact in retrospect, whereas the term ‘satire’ can be arguably swapped for ‘accurate’. Revolution in any form is a frightening prospect to consider, but They Live advocated it long before the idea entered the idea of political discourse.

THAT WINDOW SCENE

It starts off so ominously problematic. The garishly unsubtle body language between Piper’s Nada and Meg Foster’s Holly has all the implicit tropes of misogynistic 80s sex scenes. The lyrical innuendo is hard to swallow, made only worse by their eye contact that was no doubt described in the screenplay as ‘smoldering’. Piper’s eyes stalk Foster’s frame up and down with a predatory intrigue while Foster obsequiously assures him- repeatedly no less- that he is in complete control of the situation. One can be forgiven for expecting an ersatz approximation of Kenny G inspired sax to kick in as they make their moves, but instead this happens.

Didn’t see that coming!

THE FIGHT SCENE THAT GOES ON FOREVER

You kind of just have to appreciate the audacity of it. The back alley scrap between Nada and Frank is jokingly, albeit endearingly, referred to in cult cinema bubbles as one of the best fight scenes ever. The earnestness of its stumbling cinema vérité style delivery conveys a commitment not just to the story and it’s existential threat, but to Nada and Frank’s still burgeoning relationship. Piper and David spent an inordinate amount of time together off set, in character, to get the duality of their moods as synchronous as possible. This fight goes a long way towards creating that bond. Even after it seemingly ends for the umpteenth time Nada is committed to compelling Frank to just put on the glasses already. Is he doing it out of stubborn, if wounded masculinity? Is he doing it due to genuine concern for the well being of his blissfully ignorant but no less abused friend? Is his obstinate desire to prove to others and himself that he’s not crazy short-circuiting the internal systems that dictate restraint? Is the Venn diagram of all of those theories a perfect circle? In all cases the answer is yes. With each redundant blow stricken upon two fools exhausted beyond a coherent plan of attack beyond lunging at each other, one can’t help but develop a certain fondness for the two of them. Sure they are (sort of) trying to kill each other, but like Casablanca only stupid, you can tell it’s the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

WHAT DIDN’T WORK

THE FIGHT SCENE THAT GOES ON FOREVER

But also, guys, move it along here. This fight lasts longer than the entirety of the Confederacy. It ends several times over, more often than not with Nada or Frank on their ass, effectively neutralized, only for them to get up and pull a Rocky Balboa. Even Rocky hears the bell at some point. There’s knees to the head, kicks to the groin, several suplexes, a number of brief and increasingly absurd breaks for them to catch their breaths; and then, just a lot more of it. It wears so frustratingly on your patience because you know exactly where it’s going: Frank eventually will put on the sunglasses and see the monstrous alien ghouls for what they are. Just do that already my dude! The fight scene is really just a lazy mechanism to reach an expository part of the story required to shift into the third act. This is totally fine, and filmmakers are well within their rights to dress up scenes that amount to little more than window dressing. But the sheer lack of restraint and adolescent wish fulfilment crosses into obnoxious well before the 5:23 long scene concludes. Piper and Frank allegedly rehearsed the scene in the back lot of Carpenters office for months, with Piper even offering to demonstrate on Carpenter what exactly a suplex was. Carpenter, wisely perhaps, just offered to take his word for it and let them add it. They added several. The part where Piper seemingly breaks character upon accidently smashing a car window is actually pretty funny and sweet. But still, we’ve got places to be.

THE SUNGLASSES

I get that they are more or less the crux of the film, but any story that is so heavily reliant on a maguffin is asking for trouble. That such a banal object has to do so much narrative and rhetorical heavy lifting while many characters just observe, dumbfounded and nearly as inanimate at times, doesn’t make for compelling reveals. The scenes in which Piper observes the inverted and coded world, replete with space monsters for the first time, is striking in its blandness. What the narrative wants to showcase, especially towards the end, as a secret invasion isn’t depicted much beyond its ambient bureaucracy when looking through the glasses. The narrative background of a makeshift chemistry lab and assembly line operating out of humble church basement is also random enough to strain credulity. One thinks of the word salad explanations for similar plot devices such as flux capacitors in Back To The Future and dino DNA in Jurassic Park, and the didactic effort gone into at least kind of explaining these works of fantasy. In They Live, the sunglasses just work, for… reasons. That may not be the most cardinal of cinematic sins, but the gap between input and output for a device the fundamentally changes everything is a little too insurmountable. On a thematic level it’s also problematic that the sunglasses render everything in black and white. If the glasses are meant to be a vector for spiritual and mental awakening, it would be more illustrative to have the sun glasses reveal a world of vivid color, contrasted against muted sepia and marzipan tones of the regular world. For something meant to be literally and thematically clarifying, it actually muddles the message a little.

NADA’S KILLING SPREE

Parts of They Live’s story, beyond the over arching opprobrium against weaponized income inequality and Reagan era propaganda, often just doesn’t really know what to do with itself or where it wants to go. This is no more apparent than in the cop fight/bank shoot out. The sloppy mixture of almost non-sequitor pacing in the scenes and the ridiculous escalation in Nada’s actions is too galling to ignore. An unlucky in encounter with a couple of cops starts off stylistically inconsistent right from the get go with the officers aggressively accosting Nada while also urging him to calm down. After Nada kills the cops/alien ghouls he grabs their shotgun and tries to escape. Ostensibly he is trying to flee from any more unwanted attention, which would make sense. However after a wrong turn into a busy bank, he just fully commits to blowing away any of the aliens he can identify. At best this an ‘in for a penny, in for a pound’ mentality, but even that is a generous reading. Having just acquired some fire power seconds ago there is no way a bank shoot out was on his agenda, and yet after the briefest of contemplations he becomes a full fledged artillerist and opens fire. The famous ‘chew bubble gum and kick ass’ line is in part so well known for how bizarre and out of place an opening salvo it is. It’s emblematic of the scattered and incoherent tenor of the whole sequence.

THE ALIEN SPACE PORT

Or the alien underground bunker? Or fancy ballroom? Or- is there a TV station operating out of the upper floor of, wherever Nada and Frank are? Where exactly are they? A desperate and rushed infiltration into the alien base of operations leaves the duo understandably a bit disoriented. One sympathises as the film, under the duress of reaching the end of it’s limited run time perhaps, seems to squeeze disparate story threads and physical spaces into one awkwardly imagined logistical structure. Innocuous maintenance passages give way to a regalia dinner party showcasing the upper echelon of alien overlords hob knobbing with treacherous human dilettantes. As the humans give genuflecting speeches to their masters the aliens observe with insolent glee. Moving on from there Nada and Frank continue the tour and find a space port to teleport aliens to and from the Andromeda galaxy via some fancy matter transporter. What? As they work their way up they stumble upon a bustling, but seemingly benign TV broadcasting station populated with average workers. This is narratively convenient as Nada plans to destroy the satellite dish broadcasting the aliens’ subliminal messages but it’s pretty out of left field. Are the employees too in cahoots or comically unaware of the massive alien infrastructure just below the break room? It doesn’t seem all that odd to the workers seeing para-military goons hunting down our heroes as they hurry down the halls. The labyrinthine, rubrics cube like make up of wherever they are is emphasised by the films roguish sense of humour when, in all of this mess, Nada and Frank just can’t seem to find the roof.

HOLLY KILLS FRANK AND IT’S PRACTICALLY OFF SCREEN

Super rude. Bad form!