Examining The Legacy- And Necessity- Of Bizarre Ride II The Pharcyde

Decades Later The Pharcyde Debut LP Remains A Vital Portrait Of How To Navigate The Times

Tristan Young @talltristan

Bizarre Ride II The Pharcyde is a record of impulses. It speaks in extemporaneous thoughts, and stream of conscious vignettes. The ad hoc and improvisational breeze in which the members of The Pharcyde communicate belie an unserious and capricious look at the society in which they lived. When one observes that society with any kind of interrogative glance it can be hard to reconcile the casual and even delinquent swagger they so naturally exude with the realities of America’s relationship with the black community in the 90s (any era really). The dystopian injustice of Rodney King’s assault in LA brought to the forefront the institutionalized severity of police brutality against minorities, and how such conduct was seemingly inoculated from recourse. The capital C conservative modern agenda that was defined by Reaganism and perfected by Bush terrorized and demonized black neighbourhoods with their Orwellian wars on crime and drugs. Suburban America had yet to fully consider the extent to which impoverished communities with high crime rates were the result of maliciously engineered government policies, and not merely borne from draconian ideas of moral failings. The meagre response to the aids crises disproportionately impacted minority and poor communities. In short, the young men in The Pharcyde, still very much in their formative years, had a lot to be angry about.

They didn’t really seem that way though. Their music was not an expression of the frustrations they faced, at least not on a strictly textural level. Furthermore it was not a statement that seemed compelled towards grand oration to match the urgency of their time. Instead they were content to ably and vividly litigate their inane and at times surreal day in the life theatrics. This drastic shift away from the ascendant and more jingoistic gangsta rap- itself a much more literal and very much needed response to systemic racism and oppression- put The Pharcyde into something of a class of it’s own. That unique and comparatively refreshing nature drew praise immediately, and it’s esteem has only grown over time. However a slight shift in perspective and attempt to understand the nature of their satire reveals an album that was very much motivated by moral commentary. They knew what they wanted to say, and how they wanted to say it; it was on the rest of us to try and keep up.

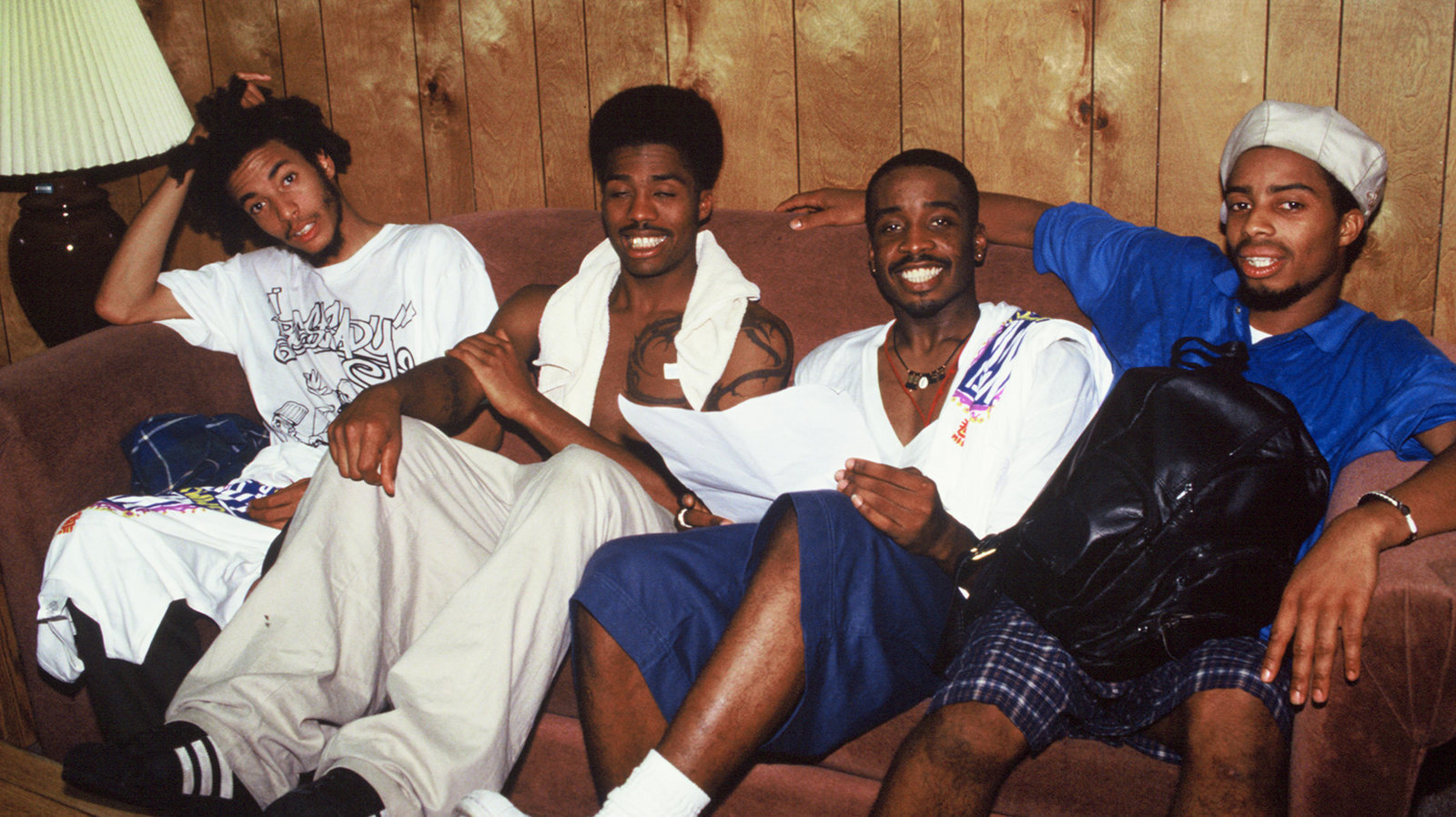

Much to the chagrin of prominent 90s political culture war narratives, the story of The Pharcyde began with a school teacher. Reggie Andrews was a local high school educator in South Central LA. Within the community he served he was legendary for his efforts and outreach to provide opportunities to students in the district to learn about and develop musical skills. Andrews had many pupils; one of his most promising was Juan Martinez, who the public would soon come to know as J-Swift. Assured of his potential, Andrews put Swift in touch with a few dancers dipping their toes into the rapidly evolving SoCal hip-hop scene. Swift met Trevant Hardson aka Slimkid3, Emandu Wilcox aka Imani, and Romye Robinson aka Bootie Brown. The three of them had met in the late 80s, worked on various musical projects and even spent some time as back up dancers for In Loving Color. Brown was also a back up dancer for Derrick Stewart aka Fatlip, who they also brought into the fold. With four emcees and a DJ, the core team moved into a house together in Inglewood and started work on their debut, which would become Bizarre Ride II The Pharcyde, released in November of 1992. It should be noted that the group’s first DJ was actually Mark Luv, but that was when the team was still very much primordial. For the intents and purposes of their first LP, it’s J-Swift we discuss.

Upon its release, the hip hop community writ large was already accustomed to the prominence of gangsta rap, especially from LA and it’s surrounding areas. 2Pacalypse Now completely reshaped a landscape that was already being altered by Public Enemy, NWA, and Cypress Hill; that trend would be accelerated by Wu Tang Clan and Nas a little later in the decade. As one of the most heavily dissected and interrogated sub genres of music in the last half century, very little needs to be said at this point other than it was fierce. The Pharcyde however, were anything but. Like their name implied they took a farcical, light hearted approach to hip hop as it bisected it’s way through dance culture. Prominent influences and progenitors like De La Soul or Native Tongues exist, but Bizarre Ride became the monolithic point of reference for this narrow niche within hip hop. Call it slacker hip hop, daisy age, whatever you like. Their animated verses were defined by levity, and self-deprecation. As Slimkid3 recalls in Oh Shit one of the many instances the group details about them crashing and burning with women, his frame of reference builds to, “Luke Skywalker ain’t a sweet talker so I got ill with my light saber that came in one fancy flavour”. They have a predilection for comical swiping at each other with burns like, “Ya mama looks like she’s been in a dryer with rocks”, in Ya Mama, but they are just as quick to turn those incisive barbs inwards on themselves. Fatlip’s passage in Passin Me Bye, “Then I signed sincerely, the one who loves you dearly, PS love me tender/ The letter came back three days later: Return to Sender, damn”, reveals a team comfortable enough with each other to open themselves up to such maligning, and even encourage it.

Being the aspiring and neophyte team that they were, The Pharcyde of course didn’t completely wallow in self-pity. No matter the breadth of comedic material to be mined from their clumsy failures, Bizarre Ride is not without it’s hype tracks. In the sweaty and bravado infused horns of I’m That Kind Of N***a Fatlip wastes no time comparing his potential and future to the greats, “I fix my funk like Thelonious Monk”. He then goes on to assume the mantle of Lionel Ritchie back when such boasts were still in vogue. Overlaid with Swift’s rolling bass and peacocking rhythm they assert their mastery of not so much genre or dance, but trash talking. They take faking it till you make it and turn it into an exquisite skill set. Imani will steal your girl, Slimkid3 will channel his inner Al Capone in a confrontation, Bootie Brown, ‘kicked your daddy in the nuts/ that’s why your mental state was fucked before you hit you’re mama’s guts”. It goes on like this.

Return Of The B-Boy makes an even more compelling, and joyously celebratory case for The Pharcyde’s earnest belief in themselves. Far from delinquent aberrations dicking around in the peripheries of alt hip hop, they cast themselves as the new standard bearers being passed a torch that so many before them proudly carried. With an RnB infused up tempo dance beat that nearly 30 years later still sounds future perfect, the team curates an inspiring collage of hip hop and dance music throughout the 80s and beginnings of the 90s. Slimkid3 references Sugarhill Gang’s Apache. Rapper’s Delight gets its moment too, as does LL Cool J. The iconic phrases are merged together through interstitial allusions to cultural markers in hip hop; the sheer magnitude of it would be staggering were it not for the economic efficiency of it all.

Most relevant is the passage, “west coast is on fire/we don’t need no water let the motherfucker burn”. It’s an obvious, if updated pillage from The Dynamic Three’s 1984 single, and a towering presence over classic hip hop even today. Consider however the manner in which The Pharcyde appropriates and paraphrases it to suit their context. The album came out not even 6 months after the Rodney King riots literally burned parts of LA to the ground. The event was disingenuously used as fuel to further vilify the black community, as if the Boston Tea Party didn’t do exactly the same thing when it became apparent to the extent their interests were not being represented centuries ago. The Pharcyde uses the phrase as part of a compendium to show not what had been destroyed but what the black community had created over the course of a decade. The Pharcyde collects these living artifacts as a monument to the black community’s creativity and contribution to American culture, a legacy far more enduring and necessary than the loss of any physical property.

Bootie Brown said he wanted to rap the way he danced. That idea translates into short bursts of concentrated charisma, very much dependent on the synergy of those around him. While Fatlip is legendary as a battle rapper, none of the team really carried the moniker of group leader. Instead they bounced verses off each other. Those not in the forefront were constantly shouting encouragement or comical disparagement from the background, as in the raucous egging on in Officer or Ya Mama. With their tracks designed around the interlocking efficiency and dependency of the group as a whole, there is a less of a coherent narrative across each track; not exactly the conditions for hi concept story telling or arched thematics. Instead The Pharcyde tells their stories through highly didactic anecdotes. The subject matter may be of similar variety but they are all charmingly (mostly) isolated slices of gossamer. On the DL has a frankly ridiculous and weirdly vivid tale of waking up next to a girl and still far too horny to handle it. In Officer Imani, like the rest of the group, recount the reciprocal and juvenile cycle of antagonism between them and the cops, “Away to our destination, no licence no insurance, not even registration, tags on the plate say December 82/ car’s so dirty it looks gray but really it’s blue”. They all have stories that lead to police harassment and they are all as ludicrous. Fatlip has a surprisingly earnest memory in Oh Shit of an unexpected sexual encounter with a trans person, for no real reason other than that life is strange sometimes. That acquiescence to the randomness of life informs their improvisational approach and their chaotic but brilliantly purposed energy. Later on, taking such conceits to their logical conclusion, all four of them skirmish in the age old battle that is Ya Mama, culminating in threats to Ricky Bell from New Edition and the delightfully odd line “Ya mama’s an extra on the Simpsons and shit”. As the Genius annotations succinctly describe it: most disrespectful line in the entire song.

Considered to be one of the best hip hop songs of the 90s, there’s not much more that can be added here regarding the impact of Passin Me Bye. Still, it’s worth exploring how the synthesis of bemused self owns and hype track flexing results in its rightful place as the centerpiece of the album. Each member of the team relives their own tribulations of spectacular failure when it comes to courting someone out of their league. This time there is more of a specific through line in the verses as oppose to incidents isolated in a vacuum. With a reduced tempo and more deliberately subdued lexical flow, they all seem intent on one upping each other in who has the more pathetic story. Bootie Brown had a hopeless crush on his school teacher, Slimkid3- who is shockingly good at actually singing here- remembers a school yard friend who has moved on now that she is, as he puts it, “highly edu-ma-cated”. Imani, in an unexpected moment of self-awareness, understands that as much as he wants, it’s not going to work out between him and his love interest. Each passage is increasingly more forlorn, each trying to out do each other. In execution Passin Me Bye humanizes a group of individuals that previously were all too happy to be caricatures, while finding creative ways to purpose their unrelenting drive.

Swift’s spritely beats were comprised of bright and buoyant bass and brass, see the invigorating pulse of I’m That Type Of N***a. The blossoming zeal and runaway excitement of Bootie Brown chasing after a horn crescendo in Soul Flower (remix) is a marvel. The excitement seems to plateau until Slimkid3 ups the ante with, “Souped up on the beat like a bowl of chicken noodles, I love Spanish dishes, but no, I’m not menudo”. Remember that earlier point about levity. Return Of The B-Boy is genre spanning high fidelity trip of homages to hip hop pioneers with bass smoothed out to such a polish it’s almost slicker than it’s subtly deep house synth. The queasy and nebulous brass in 4 Better Or 4 Worse previews early in the album Swift’s blues and jazz influences. While it registers as somewhat perverse in that track (to match some questionable, predatory subject matter), On The DL and I’m That Kind Of N***a expresses these influences in more playful terms. The record is also a diverse sampling of late 80s DJ scratch culture, contributing to the manic energy on Oh Shit and Pack The Pipe, but also the scattered confusion brought about by deflated introspection in Passin Me Bye.

Swift also had a savant’s ear for samples, some obscure enough to subtly infiltrate a beat, others becoming focal points of a track. James Brown, back when he had the JB band pops up several times in the album such as I’m That Type Of N***a or Officer. The filigreed piano of Blind Alley by The Emotions gives 4 Better Or 4 Worse an energetic but unassuming pulse. Passin Me Bye is a compositional beast with samples from Quincy Jones, Jimi Hendrix, and Whodini. While that last name may not be as iconic as the others, Whodini is much more of a kindred spirit in line with the intonations of The Pharcyde. Whodini’s Five Minutes Of Funk’s main key board sequence gets a major up tempo face lift and becomes the cheerful core of Soul Flower (remix). Swift takes Pack The Pipe through an absolute spectrum sampling the lush and nimble Autumn Serenade by John Coltrane and Johnny Harman, essentially pulling a straight lift from the bass. In the same track it also integrates Jump Around by House of Pain. This may seem like an obvious go to for several decades by now, but when Bizarre Ride released in 92, Jump Around had only released a few months earlier. It’s moves like this that illustrates Swift’s forward looking sense of taste and also just pure adventurism.

The schematic structures of Bizarre Ride- the verbose inanity and Swift’s stellar production- gave the group a unique voice, but it’s the subversive moral positioning they articulated with that voice that makes the experience so special. It’s not exactly obvious at first and certainly requires some perspective flexibility, but this was already an album of technical gymnastics so it seems rather fitting. In Officer, Slimkid3 comediclaly laments, “My tail, can’t go to jail cause it’s wack/ what would happen to my girl and my record contract”. His flippant resignation to the day to day realties of police harassment and racial profiling is capped with the playfully silly closer, “um, were getting pulled over, we’re going to jail/ yeah you guys are definitely going to jail”. Earlier in the improvisational skit If I Were President the team sings together, goofily tripping over their words, “if I were president, I would not carry, oh no spare change/ I would just rearrange the whole government structure/ cause there seems to be something messing with the flucture of the money”. The album takes a darker turn with Fatlip phone stalking a woman as part of joke gone way too far in 4 Better Or 4 Worse.

None of this is depicted very seriously, because it’s not taken seriously. Violence against women was not treated with the urgency it needed to be in the 90s. Police brutality was laughed off as anecdotal at best. Pop culture activism was barely cognizant of the increasing income gap emerging 30 years ago, even if more counter culture and cult projects like Videodrome or They Live had caught wind. If the systemic structures that had the power to do something about these malignant issues couldn’t care less, why should The Pharcyde? Instead they channel the wilful ignorance and condescending denials that so much of the world propagated and mirror it back onto us. When hyperbolic skits show us our own lack of earnest attitude or even basic empathy, it looks ridiculous. It is ridiculous. The Bizarre Ride is a satire that highlights our collective failure to treat these issues with the seriousness it deserved. The joke is not on them, but all of us, and it should be less funny the more you think about it. The problem is no one thought about it that much.

As such, The Pharcyde is remembered for the things that of course it is remembered for. “People look at every day situations and say damn! We just say haha chill out”. That quote from Imani is about all you really need to know about Bizarre Ride II The Pharcyde, but there is so much beyond that. Perhaps its genuinely unique and deftly illustrated approach to the lighter side of hip hop proved too affable for people to think that maybe there was more to this album that met the eye. That it is remembered with such storied reverence in 90s hip hop is a fitting legacy but one wonders if it is the legacy if should have had. No matter what the medium, comedy is about taking risks. The risk this album took was perhaps greater than the group could have understood at the time: Making a good joke, but to everyone that heard it, a joke nonetheless.