Death Proof Is A Brilliant Essay On The Evolution Of Film And The Women In Them

Yes, The Grindhouse Movie With The Car Chase

Tristan Young @talltristan

You ask anybody about Death Proof and you’re bound to get any number of answers that can be traced through predictable lines. A blasé response being something along the lines of ‘oh that Grindhouse movie’. A more appreciative and first hand remark might mention the car chase or that one stunt near the end. More often than not however you’ll get an answer like this: “What’s Death Proof?” This is as tragic as it is unsurprising. The black sheep of the Tarantino movies, a distinction he himself has unceremoniously given the film as he has stated it is the least favourite of his projects, Death Proof has been swept into esoteric niches of cult cinema without ever really being given a fair shot at a broader audience. Part of this is due to its 2007 dual theatrical release along with Robert Rodriguez’ Planet Terror as part of a Grindhouse inspired double bill. That you saw them both back to back in the theater (remember those?) resulted in both films being edited down to a little over an hour, truncating and blunting the merits of both. In the case of Death Proof, Tarantino’s signature and axiomatically indulgent dialogue and the sprawling scope of the climax were not fully integrated.

The Grindhouse double feature came and went from the cinema with little impact beyond the retrograde novelty of drive-in nostalgia. Death Proof went on to be the only Tarantino film to date not to be nominated for an Academy Award. By obvious virtue of them being released together under the auspices of an bygone sub genre with little current mass appeal, both films were dismissively considered to be fun, if fleeting diversions, and little more. To be sure, this is a largely fair critique of Planet Terror, a superfluous zombie film that recreates the aesthetic of a Grindhouse gore fest but does little to ruminate upon or extrapolate on the utility of the sub genre. That Death Proof is looked upon in the same perfunctory light does it a huge disservice and underscores a gross misreading of the film. For all of the sepia toned lighting, Vanishing Point references, and sporadically shocking bouts of violence, Death Proof is vastly deep and nuanced film with far more to say than one may initially think. Indeed it is one of the most creative visual essays about the very nature of film making, not just as a process, but as a cultural commodity, that one can study.

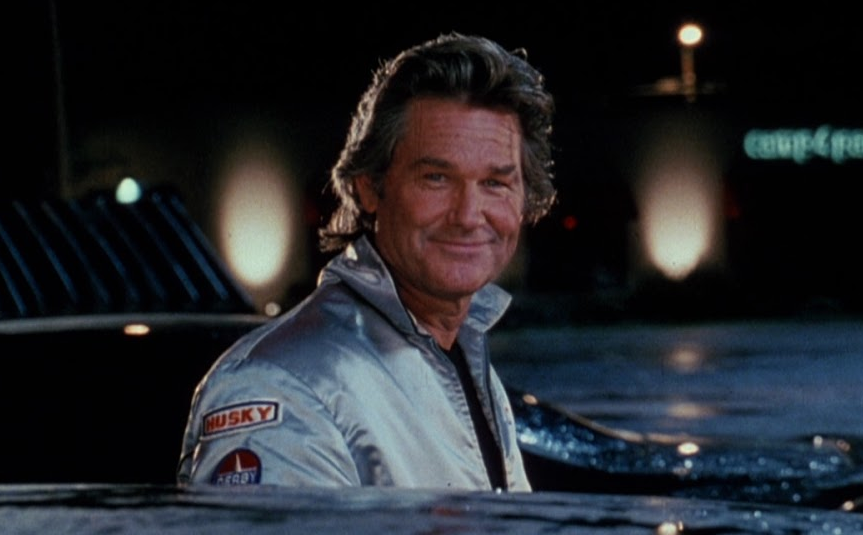

Death Proof has a simple if eccentric story line, but it’s worth going over in a bit of detail. A group of women- Julia (Sydney Tamila Poitier), Arlene (Vanessa Ferlito), and Shanna (Jordan Ladd)- introduced as being life long friends get together for a night out on the town in Austin, Texas. The plan is loosely designed around some leisurely bar hopping; nacho, margs, maybe a bit of hard liquor- one of them is on vacation after all. Meet some friends to pick up some weed, and then it’s off to lake LBJ for the weekend. The steadfast rule of no boys being allowed is wavering. One thing that was not part of the plan is an encounter with Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell). Stuntman Mike is something of a living fossil from another era; too old by a margin to be in a bar with a bunch of 20 somethings, acutely out of tune with the cultural norms that define casual coolness, and oddly verbose in a strict, pedantic kind of way. It all builds up to an earnest but jarringly peculiar individual. Nevertheless he strikes up conversations with our characters, sometimes clumsily, sometimes in manners that are unnervingly convincing.

The bar shuts down, everyone parts ways, and the girls drive up to the lake assuming their strange little sojourn with Stuntman Mike has concluded. Mike has different plans, for he has been tracking them for days, stalking them in his 1971 Chevy Nova which just happens to be reinforced to hell and back to withstand nearly any impact. He refers to it as death proof. Later on he amends that statement by detailing that in order to get the benefits of the car being death proof, you really have to be in his seat. It’s a point he proves with stunning savagery when he tracks the girls down on the highway and slams his Nova into their little hatch back, essentially liquefying it. Julia’s leg comes right off; Arlene’s face is disintegrated under a tire. It’s gruesome. The implication from the attending police investigation, featuring the Sheriff and Son #1 from Kill Bill, is that this is how Stuntman Mike gets off. They may not be able to prove that what looked like a car accident was actually an act of sinister premeditation, but they will sure as hell make sure it doesn’t happen again in Texas.

Flash forward to Lebanon, err, Lebanon, Tennessee that is. Stuntman Mike has a new death proof car in the form of a foreboding 1969 Dodge Charger, and a new set of women to viscously antagonize. This time the group is comprised of film crew pals Kim (Tracie Thomas), Abernathy (Rosario Dawson), Lee (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), and most crucially- Zoe. Zoe is no fictional character but rather real life stunt person extraordinaire Zoe Bell, playing herself. Bell was Uma Thurman’s stunt double in the Kill Bill films and Tarantino was so impressed with her work, he opted to create a role for her in which she simply got to be herself. Her innate talents would be put to good use later on in the film. Stuntman Mike once again stalks his pray, waiting for the right time to strike in his weapon of a vehicle. He finds his opportunity on the back streets of Tennessee. Zoe, visiting from her home in New Zealand, has a very specific and slightly lunatic request. Being the gear head she is, she wants to test drive a 1970 Dodge Challenger with a white paint job. In other words, the legendary Vanishing Point car. However merely driving it won’t satiate her desire, after all- like all stunt people- she’s a little crazy. With Kim at the wheel and Aby in the back seat, Zoe gets on the hood of the car as it zooms along the roads, riding it like something of a ship’s mast with nothing more to hold onto besides a couple of belts attached to the door frame.

It is here where Stuntman Mike strikes; only this time it doesn’t go the way he planned. He repeatedly slams his Charger into their Challenger with an absolutely terrified Zoe still on the hood of the car, being knocked further and further towards the edge. It needs repeating that this is a wholly practical stunt and one of the most impressive of the sorts ever committed to film. As the two beasts repeatedly smash into each other at unsafe speeds, Zoe is on the hood trying to find something- anything- to hang on to before she is rendered upon the asphalt. Death Proof is absolutely required viewing material for this stunt alone. That Zoe miraculously survives the ordeal is lingered upon for only a brief but sweetly salient moment. Once their relative safety is established Zoe, Kim, and Aby have only one thing in mind. Track down the fleeing Stuntman Mike and get bloody revenge. Do they ever. After a sprawling car chase that puts Bullet to shame (again, all practical), they flip his car and put him down for good. High fives all around.

Why did Tarantino tell essentially the same story twice? Why forgo a standard three-act story and opt instead for an extended two parter with a brief interlude that repeats itself, even if it ends differently? Therein lies the subtle genius of Death Proof. Tarantino tells the same story twice to create a visual metaphor for how the film industry has changed, not just in terms of its technical evolutions, but how gender roles, definitions, and opportunities have progressed since- you guessed it- the Grindhouse days. The first sequence recreates (as best it can) anachronistic production techniques, but also subjects the female characters to all of the objectification and over sexualisation that was endemic of that era. Contrast those sentiments with part two of the film. Starkly modern production techniques alter the look and feel of everything. Kim, Zoe, and Abby are defined not by their looks or bodies, but by their autonomy. In doing so, Tarantino solemnly eulogizes the Grindhouse sub genre and era’s place in history but celebrates the manners in which we have moved on from it.

A series of compare and contrasts help illuminate the degree to which Tarantino creates a mirrored dichotomy in his two main sequences. Perhaps most notable initially is the film’s quality and color grading in both parts. The first has muted, sepia tones. The production team physically scraped the 35mm film (Planet Terror was shot on digital which tells you all you need to know about it’s commitment to authenticity) to give it that analogue and cozy degraded quality which further muddies the faded beiges and browns. Sequence two is pristine and crisp. The film is designed to hide this jarring transition through a brief black and white period to create a gulf between comparisons, but it’s still hard to miss. Like jumping 40 years in the future, the film stock pops with neon yellows and pinks. The vibrant blue Tennessee sky glistens across nearly every scene in the second part.

The technical details extend to the film’s relationship with music. There is already something old school about Julia being a radio DJ from the onset of the film. These dated incarnations of mediums and consumption are further exhumed with the constant use of the jukebox at one of the bars the girls visit. Notice that one of the songs played on the box- The Love You Save by Joe Tex- is also a song Lee plays in sequence two. In Lee’s case however, she is playing it on an iPod (note that circa 2007 when the film was released a simple iPod was hot shit). Later on in sequence one Julia calls into a radio station to get them to play a song. What’s more last century, time capsule-esque than calling into a radio station to hear a song? Sequence one does not take place in a distant, forgotten past; it’s all more or less present. Yet the only connection to the mid 2000s the film lingers on are in taciturn and melodramatic moments where Julia hovers over the glow of her flip phone screen.

While miles to go still doesn’t cover the extent to which Hollywood (most industries, really) needs to get it’s act together in regards to how it presents women as objects of manipulation and predation, one can certainly see the progress made when looking back on pop culture films of the 60s and 70s. Death Proof puts this contrast into stark relief. Stuntman Mike’s cutely endearing monologue about all the shows he used to work on in the old days, the all or nothing days, is intended as a meta commentary of how the roles and markers of various depictions in film have evolved. Consider those depictions in sequence one. We observe a gallery of insipid and vacuous men hitting on the girls in predatory ways, trying to get them as drunk as possible on round after round of shots. They refer to the girl as “bitches” in frustratingly caviller ways. This corrosive behaviour is reinforced by the social structures all around them. When bar owner Warren (cameo by Tarantino) brings over a round of chartreuse- why chartreuse? - Julia boasts, “When Warren says it, we do it”. It seems completely lost on Julia that she plays into this right after pining via text over a would be lover that is clearly stringing her along if not flat out ignoring her. That this phantom character is also a high-powered movie producer reinforces the toxic, patriarchal hierarchy that men in Hollywood have been able to exert over women for so long.

Compare this to the way our characters interact with men in sequence two. Abernathy is able to exercise a set of persuasive gymnastics around the person selling the Dodge Challenger, ably convincing him- manipulating him really- to let them take the car out on their own (although it needs to be mentioned that she does so in part through a creepy innuendo involving the car seller and poor, oblivious Lee). Furthermore, imagine hypothetically those same piss ant goons from sequence one trying to ‘seduce’ a character like Kim and wonder how far would they get. Likely not very. The most striking contrast in this regard is of course how Stuntman Mike handles both sets of characters. In sequence one he has an oddly destabilizing sense of intrigue to him. His at times overwhelming verbosity, that strange sneezing moment, and his domineering John Wayne impression. It leaves an impact, at least on Arlene. Then he murders them. The characters in sequence two however ably get the upper hand after he fails to kill Zoe. Kim shoots him, they attack him, chase him; reduce him to a sobbing, blathering fool begging for mercy. They of course are decidedly lacking in mercy.

The sequential differences that contrast movies from one era to the next are most acute in the depiction of our two groups of main characters themselves. Right from the get go characters like Julia and Arlene are hyper sexualized. There are gratuitous camera angles, Arlene’s lap dance scene, and a fixation on Julia’s legs. Indeed she is seemingly and cruelly punished for such sexualisation on a rhetorical level when her leg is ripped off during the violent crash at the end of sequence one. None of this exists in the second sequence save for meta commentary. These characters are not the objects of hyper sexualisation in movies. They make the movies. The only potential exception is the suggestive cheerleader uniform that Lee is wearing, but it actually reinforces the point: she is in wardrobe, she is depicting something fictitious in a world that aims to present gender in a more honest and balanced way. Of course she would seem a bit tonally off in this context.

The most Tarantino-esque scene of the film, the round table dialogue scene, has Kim, Aby, Zoe, and Lee discussing a litany of non-sequiturs: Kim owning a gun (“check it out bitch!”). That time Zoe fell in a ditch, pranking Lee, how they are going to pull off this Challenger caper. Not once do they discuss a man. When they do in a previous scene, nearly all of them discuss their current relationships, but in most cases the conversation steers towards how they can force the terms of such relationships to play out to their satisfaction. This depiction of women intersects not only with the film’s running meta commentary but with its most distilled statement on the old and the new. Stuntman Mike is a fictitious and patriarchal representation of how films used to be made. Zoe Bell is a real life stunt person- and bourgeoning star in her own right- that represents how film, the characters in them, and those who make them have begun to move beyond such restrictive models. To reiterate, Hollywood still has so much work to do in this regard, but even watching the treatment and depiction of women even in 90s cinema versus Death Proof shows how much the Overton Window has shifted.

You can’t help but wonder if Death Proof were released in our current and needlessly polarized climate if it would draw the wrath of misogynist internet trolls, offended by the capability of woman in the face of a person as seemingly threatening as Stuntman Mike. One shudders to think of the discourse around this film being reduced to such primal and regressive fronts. More than likely though it would be just as ignored now as it was then. It may be largely considered the Tarantino underdog, but Death Proof is one of his greatest accomplishments. A film that is so much more than the sum of its parts even when those parts have one of the most death defying stunts this side of Tom Cruise. It deserves not just our respect but also an interrogative eye with the depth to match its own ambition. Also- good lord that soundtrack.