Is Event Horizon A Cult Film? Should It Be?

The 1997 Sci-Fi Horror Film never fit comfortably within Hollywood pop culture. Does it belong anywhere?

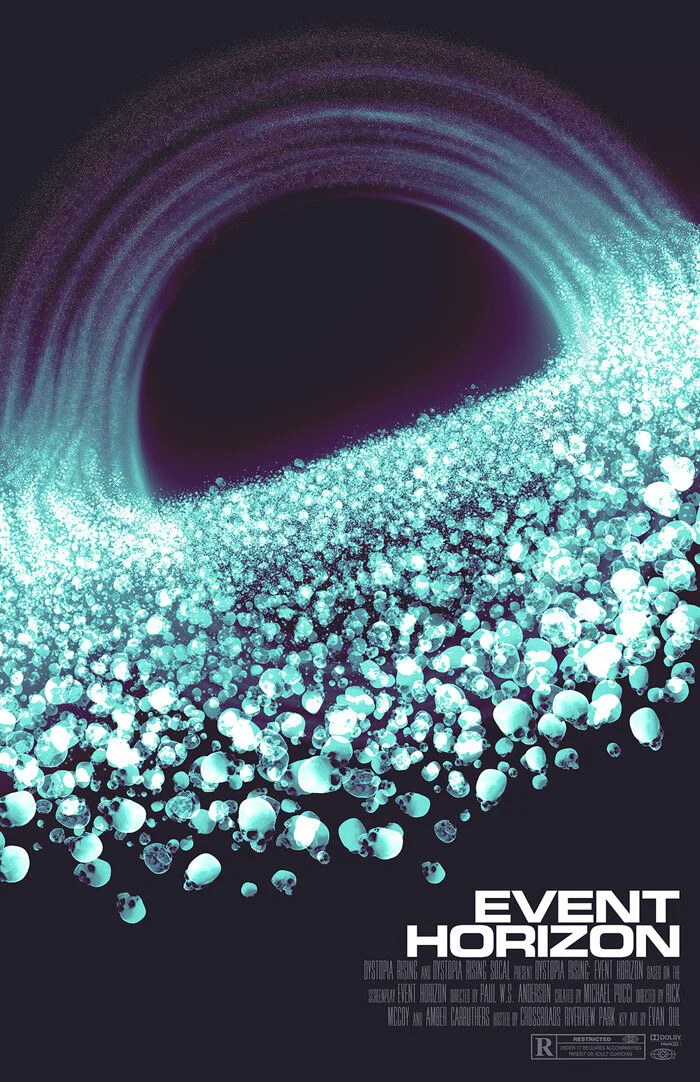

image by A Movie Poster A Day via Tumblr

Tristan Young @talltristan

Picture yourself a mid level executive at paramount in the mid 90s. Star Trek is still a viable cinematic franchise. It’s been a while since a proper Indian Jones but Titanic is in the pipeline. Life is more or less good. Then a writer named Philip Eisner tries to sell you an idea. His concept is simple: The Shining, but in space. As far as elevator pitches go, it doesn’t get much more enticing than that. What could go wrong? Well, a lot actually, as it turns out. That pitch would eventually become Event Horizon, the 1997 sci-fi horror film that collapsed not under the weight of its own ambitions, but over the precariously rickety foundation it was built upon. A lot of things went wrong for Event Horizon; very little went right. Its release was met with a critical rote and a commercial shrug. On an approximately 60 million dollar budget it, brought in less than half of that at the box office. Ouch.

Directed by Paul Anderson (not Paul Thomas Anderson, just so we are clear), the premise of Event Horizon truly was promising, even exhibiting a modicum of genuine uniqueness. In our space fairing intra-stellar future an experimental ship, The Event Horizon, skirts the issue of faster than light travel being impossible by creating it’s own black hole as a bridge from any part of the universe to another. In its inaugural voyage the vessel enters the black hole, but never returns. Lost to space, seemingly forever. Seven years later, it suddenly re-emerges in orbit around Neptune to the surprise of everyone. A salvage ship led by Captain Miller (Lawrence Fishburne) and Dr. Weir (Sam Neil) are sent to investigate what exactly happened to the wayward ship. As Miller, Weir, and their crew wander the Geiger-esque corridors of the derelict ship, evidence emerges of a horrifying slaughter that claimed the lives of the original crew. As they dive deeper into the mystery of what happened and why, the crew discovers that when the ship crossed through the black hole, it may literally have descended into hell, driving the crew insane and possibly bringing something back.

This all sounds very cool and scary! Sadly its execution was pretty notably botched across the production spectrum. From pre-production to editing, its conceptual goals and execution were never clearly in sync. Paul Anderson, having recently directed the not great but better than it had any right to be Mortal Kombat, clearly put a lot of love and effort into the project. He turned down directing Alien Resurrection and MK Annihilation- the former being not very good, the later being astonishingly terrible- to make a gore drenched horror film. That enthusiasm didn’t translate into critical or audience interest sadly.

In the subsequent years and decades however, opinions have changed around Event Horizon. While it was never able to muster any kind of begrudging respect from the most discerning filmgoers among us, an admiration for its ludicrous audacity is more common. Ask any millennial and they will openly admit its schematic shortcomings, yet can’t help but hold an ardent appreciation for it. Event Horizon has come a long way since its disastrous release, finding if not a place in pop culture iconography, then in its harder to map subterranean zeitgeist. Why exactly? Is Event Horizon a retroactively loving time capsule to a bygone and bonkers era of Hollywood storytelling? Or has it transcended mere apologist sympathies and achieved that perpetually amorphous state of being a cult movie?

image by Evan Ohl via Alternate Movie Posters

Films adorned with status of being ‘cult’ are garnered with a storied reverence, often completely divorced from the contents or merits of the film itself. The terminology and, more flummoxing, the criteria for such status is borderline arcane. There is no specific path to becoming a cult film, nor is there any kind of coronation marked by consensus. Rather the title gestates over history for certain films, until it is something that is simply understood. No one can set out to make out a cult film; it can only be observed post mortem, after an often inglorious death. Rocky Horror Picture Show is the most famous example (although being famous is somewhat antithetical to the concept), with its bespoke encouragement of audience participation and bizarre genre splicing. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is another easy example with its at the time iconoclastic shock horror. So where does that leave us with Event Horizon? While it doesn’t really follow either of the aforementioned paths, the film does manage to orbit around and weave itself through certain characteristic markers of cult films that make it at least worth consideration.

Most obviously working against Event Horizon in this regard is the notion that it was a large budget Hollywood sci-fi film, all seemingly disqualifying indicators preventing it from even being considered for cult status. Cult movies are supposed to exist outside of the Hollywood bubble, one with ossified barriers that trap in only the most clichéd and commercially viable stories and designs. Cult cinema is traditionally thought of as indie films, or from foreign countries; underfunded flops and auteur experiments, not tent pole summer blockbusters no matter how sub par. However Event Horizon is in many ways a typical summer thriller in name only, and an ersatz one at that. In reality it never really belonged in the situational context it was presented in, and the troubled production it took to get it there is in of itself an interesting story. Films that had noteworthy problematic schedules, anything that can create discourse around its production separate from the actual product, often elicits the interest of counter culture filmgoers. Event Horizon, for better or worse, inserts comfortably into this way of thinking.

While one can wonder if Event Horizon was ever supposed to even be made, it sure as hell wasn’t supposed to have been released in August of 1997. You can thank James Cameron, of all people, for that. The blockbuster of the decade, and Paramount’s ace in the hole, Titanic was slotted in for a summer of 97 release, until Cameron had to delay it to winter. Paramount suddenly had a gap to fill in their release schedule and not a lot of time to fill it. They approached Anderson, who they had been in talks with regarding Event Horizon, but little more. They gave him a proposition: they would produce the film, but only if he could have it ready by August. This gave Anderson from the time of being green lit to actual theatrical release only 10 months to make it happen. This is an inordinately short amount of time for such an effects heavy film to be put together. The tensions and compromises of this time constraint are evident all throughout the film. Anderson had to find teams that could assemble and make ready sets in only 4 weeks. He only had another 4 weeks for nearly all post-production. The spiralling opening shot of Dr. Weir in a space station orbiting earth took up nearly 1/3 of the entire effects budget. While that shot holds up reasonably well today, the same surely cannot be said for much of the remaining CGI. When the first test screenings of the film were a disaster, Anderson was left with one week to recut the film. Many established and respected production designers turned down key rolls due to these constraints. Anderson worked with who he could, struggling much of the way.

Beyond atypical or problematic productions, cult films are often referred to as such due to peculiar unknowns that surround their creation. Anything from mysterious questions, unknown subterfuge, or conspiracy theories around a film help create a layer of tantalizing obfuscation that cult filmgoers love to dissect and theorize upon. This in turn encourages audience participation and involvement long after the credits role. The Blair Witch Project for example, launched a concurrent online ad campaign with its release in the nascent days of the internet depicting the film as based on a very obscure, very true story. By the time of the film’s release some filmgoers weren’t sure what was and wasn’t fiction, and wanted to learn more.

image by Quiltface Studios via Tumblr

It’s Event Horizon’s disastrous test screening that is the source of some mystery and mythologizing around the film, for more reasons that one. Paramount executives informed Anderson, upon considerable negative feedback from test screenings that Event Horizon would need a drastic recut. Anderson was instructed to chop almost 30 minutes of footage from the film. Nearly all of the footage in question came from the satanic orgy sequences, only flashes of which survived into the final cut. We’re talking hyper-epileptic shots of ritualistic mutilation in the extreme; things like barbed wire bondage, gouged eyes, flayed skin, blood soaked penetrations, this was the stuff that was left in the film. Observations of the original cut estimated the film in that form was clearly on track for the dreaded NC-17 rating, rendering it useless for any commercial prospects. Anderson was forced to cut much of that footage, for it to never see the light of day. What exactly was in that footage that was so heretical? As fan sites have used modern tools of the internet to create montages and gifs showing the left in content in clarifying and succinct terms, we can only wonder how severe the footage was that was left out. This mixture of taboo subject matter, too extreme for mass consumption, and footage lost to the unwritten pages of history has been ripe for theorizing by cult sleuths and enthusiasts. We may never know what exactly is in the lost footage of Event Horizon, and that morbid history is part of the fun, whirling it’s devoted acolytes into flurries of ideas and fan fiction.

This in turn leads us to another mystery, one beyond the frames of the films mordant narration, and into our own reality. What, if anything, happened to the lost footage? If a burgeoning fan base had revealed the potentially longer than expected legs of the film after its theatrical run, why did we never get any kind of director’s cut? What little information we do have on the subject opens up a world of real life mystery that in of itself could be sculpted into a cinematic thriller, or at least a pretty interesting documentary. Being released in 1997, Event Horizon predates the DVD era by just a couple of years and with it the special features in the vein of deleted scenes or extended cuts. Once the physical media landscape had shifted these were fairly benign and expected features, but back in the VHS era they were quite novel and uncommon. As a result, archiving cut footage was not a duty subjected to best practices by many studios, save for the most culturally or financially relevant films. No one really put any effort into properly labeling or storing all of the extraneous Event Horizon footage, much to the dismay of Anderson.

To add further insult to industry, shortly after Event Horizon’s underwhelming theatrical run Paramount execs admitted to Anderson that they were actually pretty interested in his original cut, but yielded entirely, if somewhat reasonably, to audience impressions. Interest in releasing a directors cut was definitely there, if they could only find the missing footage. As employees of production houses, studios, effects companies and the like came and went over the years, so too was whatever additional footage that survived scattered into parts unknown. Anderson and his assistants scoured the world chasing down clues to their alleged whereabouts. They even found a VHS once years later, although Anderson lamented that the footage was too degraded to be of use to anyone. In a separate instance they tracked down a reel of footage into an abandoned salt mine in Transylvania. How on earth it could have possibly gotten there seems like a story worth telling. Anderson maintains to this day that more missing footage could be out there. Modern legends like this, equal parts plausible and incredulous, lend themselves towards that imperceptible fog of unknowing that helps cultivate the idea of a cult film. It’s a fog that indicates if people try hard enough, search long enough, they may pierce it and find the answers within.

One imagines that any notion of Event Horizon’s obscure future notoriety was of little solace to Anderson as the film floundered in 1997. Still, there is the Kurt Russell factor to consider. Anderson showed Russell the film (they would work together shortly after Anderson worked on Event Horizon on the film Soldier) in a private screening, to which Russell responded with remarkably prophetic words of encouragement. “Ignore what people are saying”, offered Russell, “In 15 years you’ll be glad you made this movie.” If the personal endorsement of Snake Pliskin himself isn’t enough to earn Event Horizon some form of cult cinema credentials, then it’s a shadow genre too inscrutable to ever hope to be understood. Surely a film that went to hell and back should fit right in.