Examining The Role Of Light In Akira

The Seminal Work Of Japanese Animation Utilized Its Visual Flourishes in Stunningly Thematic Ways

Tristan Young @talltristan

Whether you’ve seen it or not, your film going appetites, even your pop culture consumption likely owes a debt to Akira. As much as single piece of media can, it was a film that changed at the very least- a lot. No Akira: no Ghost In the Shell and no The Matrix. No Pokémon and a literal generation of its subsequent iterations and bastardizations. Intimidatingly complex, stunningly beautiful, and astonishingly violent, Akira signalled that animated films, beyond the family friendly offerings in the Disney continuum, were ready to operate in a theatre of higher and more mature discourse. The neo sci-fi epic represents a foundational epoch in dystopian futurism, modern noir, and the ever-popularizing cyber punk genre. It’s sprawling ambition and subsequent, if long shot, success in western markets introduced to half of the developed world a market and ecosystem of animation characterized by unique and intriguing styles, aesthetics and cultural themes. It bridged a gap that so many at the time weren’t even aware was there. It has become a rote cliché to examine any significant film and offer one of those ‘it’s all in the details’ kind of hagiographies. Indeed the technical intricacies of Akira and its uniquely adventurous production are legendary. Beyond the platitudes and aphorisms however, where Akira sets itself even further from its contemporaries- if it ever even had any- is the ways those technical details build not only the dazzlingly opulent aesthetic of Akira but in their own subtle regard, tell its story in a more elemental way than its characters ever could. With this in mind, it’s worth examining the role of light and its depiction in the rhetorical telling of Akira’s narrative.

The story of Akira is a thicket of dense ideas that overlap in messy and non-linear ways. To this day certain details, and what certain events actually signal is the subject of modest debate. Insofar as a film as labyrinthine as Akira will allow, a quick(ish) recap is in order. 30 years after a mysterious and horrific blast obliterates Tokyo, the shock and confusion of which kick starts World War III, the year is 2019 and from its ashes Neo Tokyo has been built. A sprawling and ominous metropolis bathed in perpetual neon light, the bleeding edge technological might of the mega city does little to hide the rampant corruption and violence that plagues its every district. Duplicitous and self-dealing politicians and ornery military leaders are mostly unable to curb the random and common violence perpetrated by all manner of gang and drug warfare. In the midst of all of this is a delinquent biker gang led by the sarcastic and rebellious teenager Kaneda. While most in Kaneda’s squad can hold their own, amongst them is the ostensible runt of the litter, Tetsuo. Smaller and weaker than then the rest, Tetsuo constantly strives and fails to prove his worth, at increasing risk to his own well being. A conflict on the derelict highways of the Tokyo ruins leads to Tetsuo being seriously injured and taken into military custody.

Under their observation they discover Tetsuo’s latent, but now metastasizing physic powers. Being such an abused and discarded member of society, Tetsuo is uniquely ill equipped to understand the burgeoning abilities growing within him. While the military has spent the decades since the destruction of Tokyo identifying and controlling children with similar abilities, Tetsuo’s powers are far too severe and unpredictable to contained. As Tetsuo takes his internalized rage out on the entirety of Neo Tokyo it becomes apparent that his powers may even approach that of the mysterious and fabled Akira- the boy who a generation earlier destroyed Tokyo. As Tetsuo succumbs to his own hatred and psychosis, Kaneda and the military race to reach him first, either to save him or kill him.

If the story sounds like an alienating multiplex of ideas, don’t worry; repeated viewing is not only encouraged but required to take in its full breadth. The film contemplates many themes and morals ranging from the role of eastern religion in an increasingly technological life to the small C conservatism of how we raise our children. Concepts of dependency and abuse on a systemic level are overlapped with the virtues of at least trying to understand and accept our place in the natural order of things. Conversely, can a natural order of things even exist in a world full of disaffected psychic monsters that can atomize small parts of the earth at will? Proto nationalism in its most militant and corrupt forms pushes up against the question of what relationship, if any, one can have with the land in which they inhabit. Many of these questions, if not out right answered (they often aren’t) are informed by a decidedly eastern cultural take on how to excavate these ideas. Like much of eastern cinema dating back to Godzilla, the trauma of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has shaped stories less focused on preventing apocalyptic disaster, but learning to exist in its aftermath.

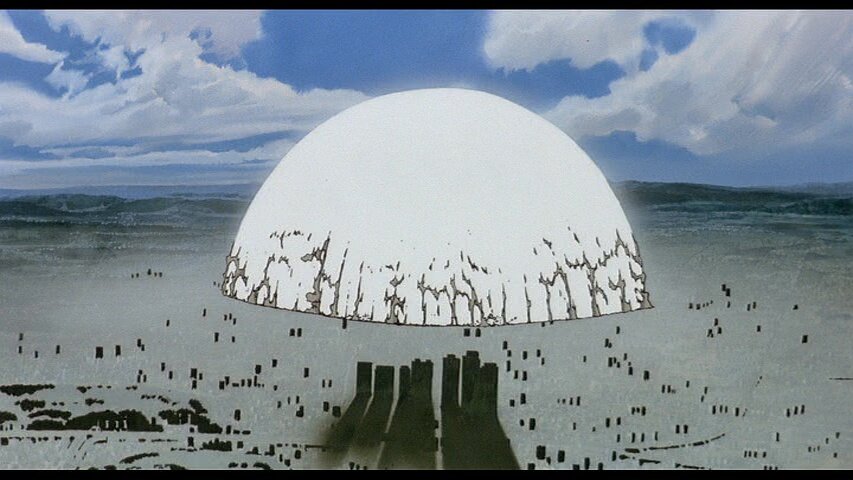

With this in mind the multiple cataclysms that bookend Akira can be considered in a purifying and transformative context beyond the obvious prodigious denotations. With these destructive spheres of psychic energy primed to do more rhetorical heavy lifting than merely liquefying Tokyo and Neo Tokyo, we can begin to understand the role light plays in Akira as a whole. Let’s first separate the two and examine the first detonation in the seconds long prologue that opens the film. With an eerily silent overhead shot of an 80s rendering of Tokyo we see modest buildings soaking in the natural sky blue of a clear day. The structures are a benign stretch of beige and marzipan stucco and concrete suggesting a banal, utilitarian urban setting. A twinkle of centralized light over the city rapidly expands at an exponential rate, engulfing Tokyo and then the entire screen in a flash. While the blast is primarily of pure incandescent white, it briefly flickers into a negative black; this inversion of the depiction of energy and light foreshadows the ominous and oppressive role it will have in Akira. The palliative and subdued hues of sunlight that are bleached out by a violent psychic eruption are one of the few depictions of natural light we will see in Akira.

From there we are introduced to the main and integral setting of Akira- Neo Tokyo circa a distant future of 2019. Few cities ever in animation or even more cinema vertié styles have ever been realized with such fidelity, detail, and aesthetic vision as the nocturnal beast that is Neo Tokyo. The roaming parallax shots of the city show layers and layers of skyscrapers stretching for miles in all directions, short-circuiting one’s conception of distance and contrast. The complex network of impossibly grand obelisks tower over a tangled web of highways that double as non-linear war zones for the torrent of violence, both state sponsored and guerrilla. Neo Tokyo is hellscape packaged as a cruelly prophetic take on futurism.

From the first intro shots of Neo Tokyo, the fading blinks of a red light over a run down bar, and the sporadic flickers within the watering hole, it’s clear that life is disturbingly different. We see that light no longer functions as the soothing balm that was suggested in the prologue. Neo Tokyo is often shown at night, but is fully draped in unrelenting neon, a scathing illustration of consumerism acting as an affront to nature. The neon light districts of Shibuya, Akihabara, and Kabukicho in Tokyo in the 80s signalled the economic come back of Japan as it spent several generations recovering from the trauma of twin nuclear attacks. It became a symbol of modernity amongst its population and re-asserting control over their nation’s manifest destiny. In Akira that modernity has been twisted and extrapolated into the conclusion of a dystopian worst-case scenario. There is no escaping from the unnatural filters of the iridescent yellows and pinks and purples. Floodlights blot out the stars, holograms strain your retinas, and skyscrapers are pillars of seemingly pure and foreboding energy. The high tech bikes that Kaneda and his cohorts ride leave hypnotic streaks of light in their furious wakes further convoluting lines of sight. One of the skyscrapers that serve as a monolithic symbol of the military’s centralized and oppressive authority is depicted as bathed in pure, blinding light, more so even than as a physical construct. Light is supposed to be cleansing, pacifying, and most importantly illuminating. In Neo Tokyo light is a trap, a web that ensnares you from which there is nowhere to hide. Like being forced to stare with no reprieve until insanity sets in, the ferocious illumination of Neo Tokyo incenses its citizens, exposing them like a raw nerve and eventually a live wire. The light is not freeing or something that you actively seek; it is oppressive and claustrophobic. There is no hiding in Neo Tokyo, no hiding from it.

Much as Tetsuo drastically upsets the balance of power and stability in the narrative of Akira, so to does his metamorphosis destabilize the role of light within the film. Multiple shots show an experimental rendering of his brain waves in the form of a kaleidoscopic pattern of circular light. With each iteration and developmental stage in Tetsuo’s mental journey, his visual base line grows more erratic and encompassing, threatening to subsume that of Akira’s potentially- a metaphor for the morally onerous scientists who study these children meagre understanding of the powers they are flirting with being upended. Tetsuo repeatedly represents a complete upheaval to that understanding through how he interacts with the light. In one of the few day light scenes we see the military throwing increasingly experimental artillery at Tetsuo in hopes of stopping him. When traditional ordinance proves woefully impotent they release a litany of personal mounted lasers at him. A symbol of the jingoistic terror the Neo Tokyo military will unleash upon its citizens, Tetsuo easily bends the arches of light around him. It is a key depiction of the light, an agent of Neo Tokyo’s Orwellian authority bowing and becoming completely subservient to the insurgent Tetsuo. More strikingly is when they up the ante considerably and deploy a satellite offensive laser from orbit to rain unrelenting destruction down on a single boy, unspeakable collateral damage be damned. Dubbed the SOL as an obvious allusion to the star at the center of our solar system, even that construct of technological terror fails to stop Tetsuo. The implication here through his interactions with sources of unnatural light is that Tetsuo has evolved far beyond the jurisdiction of any terrestrial authority, and is on the cusp of achieving god hood.

Akira’s most stark illustration of this inversion of the light dynamic is actually a much smaller, but no less chilling moment earlier in the story. As Tetsuo’s nascent powers are only just being matched by his inchoate delirium he stalks the halls of the medical detention center from which he is attempting escape. As a cadre of heavily armed guards surrounds him he stares at them with haunting intent- maybe even a touch of glee. A vibrating wave of pressurized force rips Tetsuo’s would be assailants to shreds but also shatters every light in the hall way. The environment goes from the typically sterile lights we associate with a hospital to being shrouded in pure darkness. Tetsuo’s silhouette is barely visible as he is surrounded by viscera and sundered limbs. It’s here that Tetsuo’s primacy over the light begins to truly manifest. For the first time in Akira, someone can make the lights of Neo Tokyo turn off.

Tetsuo further asserts his ad hoc restructuring of the world and the role of light to his preferences to a gluttonous and self-destructive extent moving into Akira’s third act. As his hubris and feverish mania erode what little control he had over his corporal body, Tetsuo undergoes a painful and viciously graphic transformation into something beyond human and beyond control. It’s in this climax we learn that Akira, to an extant that is arguable, still exists and returns to our plane of perception to save Tetsuo. Doing so however means Akira must aid Tetsuo’s evolution into a being of pure energy, just as Akira himself did 30 years prior, nuking the city as a result. It’s a process that is roughly akin to a horrific release of energy comparable to a nuclear explosion. Just as Tokyo was a generation prior, so too would Neo Tokyo be bathed in a light beyond its comprehension. The film strongly asserts Akira’s unconventional benevolence towards Tetsuo and all of us, but also his dominance over Tetsuo. For all of the traumatic horrors Tetsuo unleashed for much of the film, he still cowers to the awe inducing capabilities of Akira. This film backs this power dynamic again through the depiction of light. As Akira instigates the destructive process that will ultimately be his salvation, Tetsuo finds himself engulfed in a sphere of blinding light that he cannot control. Tetsuo begs in a terrified and hysterical voice “what’s happening, Kaneda, help me”. Tetsuo can’t stop this; he can’t control it, and certainly can’t understand it. For the first time since the onset of the film, the light of Akira renders Tetsuo and Kaneda at a spiritual parity, finally situated within the terms where they can reconnect with their friendship that once met so much to both of them. Tetsuo is no longer a god, just someone blinded by the gospel lights as much as everyone else.

Referencing the cyclical forces of nature that prescribe much of the cultural themes of Japanese cinema, Neo Tokyo is engulfed in this same light and destroyed just as it’s predecessor was. Tetsuo was no match for it, nor can the decadent metropolis of neon radiation resist being engulfed in something far more potent, signalling the futility in ever trying to understand such power without first respecting it. In the climax’s aftermath Kaneda and his allies find themselves surrounded by ruins and the scattered detritus that was once a global super power. It’s all just debris now. But in that aftermath we see something that isn’t really showcased at all in the entirety of Akira- natural rays of sunlight. As the last perceptible embers of what was Tetsuo fade from his reality Kaneda can observe the cleansing glow of the sun for the first time in the story. The metaphor here is obvious; that forgiveness, rebirth, and a second chance are always within reach, but it’s through the depiction of the visual language of the film that ensures this registers far more convincingly than any dialogue ever could.

It’s hard to imagine the use of light in all of its attendant forms being so successfully translated into a big screen remake of Akira, as many have proposed. The intricate color palate and specifically realized aesthetic seems too elementally affixed to the medium of animated film. This is of course true for many aspects of Akira. Exploring its use of light is by no means the only technical or artistic aspect of the film that translates into its story in such sublime ways. Its use of technology; subversions of the relationship between the natural and the artificial also dovetail in impressively specific ways with Kaneda and Tetsuo’s struggles. It’s this convalescence of ideas into something so robust that makes Akira a singular and pivotal moment in film history, and one that can blissfully be interpreted and dissected in myriad ways- but never imitated. It doesn’t need to be, as we still have a great deal to learn from it. Akira’s symbols, rhetoric, animation and themes are a wellspring of innovation and inspiration; something that becomes more apparent every time you shine a light on them.