How The Abyss Became A Microcosm For Visual Effects In Film

The 1989 James Cameron film marked the beginning of the future of effects technology, but also a window into its past

Tristan Young @talltristan

There’s something anomalous about The Abyss. On the one hand it seems like the quintessential summation of all of James Cameron’s past and future traits as a film maker. Treacherous and logistically improbable water settings. Ground breaking effects. Ardent, and in this case even saccharine anti military and colonial messaging. Michael Biehn! And yet The Abyss is also the most overlooked and easily forgotten in Cameron’s catalogue. This may be due to the fact that pretty much every other film he ever directed became monolithic markers in pop culture zeitgeist, whereas The Abyss was only just very interesting. It may be because when his other films weren’t adding iconic visual touch stones like the Queen Alien or the T800 to the annals of film history, they were making more money than god; The Abyss’, however, contribution to science fiction character work isn’t quite as indelible, and with a budget rumoured to have ballooned up to $70 million (well past it’s proposed $45 million) and it bringing in only $90 million in total, it didn’t exactly kill it box office wise.

Yet The Abyss has earned a special place not just in Cameron’s catalogue, but in the history of cinema. More so than many films of its time- of any time- The Abyss marked the end, and the beginning of how films were made. If Citizen Kane changed forever how cinematography and lighting were approached in film, as did Birth of a Nation rewrite the rules on narrative pacing and structure (although this writer or publication in no way endorses the themes or message of the that film), The Abyss marked a sea change in how special effects were handled. What was thought possible, and how it was done was completely radicalized by the special effects breakthroughs of The Abyss. At the same time, it’s a film that made use of old school, even archaic tricks as pioneered by the mentors that Cameron studied under. As such, The Abyss is a microcosm of the history of visual effects, and in large part the reason why movies look as good as they do today.

We take for granted now just how reliant film and TV is on CGI, even to the point where there has been a decades long backlash against it’s over saturation. 30 years ago film effects were tethered to what its crew could practically come up with, and the costs associated with it. But as CGI became more developed and cost effective, it became ubiquitous, to the point of obnoxious overkill. There are few examples as egregious as the Star Wars prequel trilogy, that is ostensibly just a lot of animated detritus mapped over a green screen. Things were trending that way back in 1997 with Titanic, where there were multiple scenes involving the disastrous destruction of the water logged ship rendered with computer animation. Why do that when certainly there was access to the real thing, at least for some of the interior shots? Well, it was cheaper, required less crew, was orders of magnitude safer (this is a big one), and more was possible through CGI trickery.

None of this was possible at the inception of The Abyss’ production. As a result, much of the effects in the film are very traditional, very practical, and at times very crafty. While the film takes place at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, much of it was actually filmed in a retro fitted decommissioned nuclear reactor facility in South Carolina. 7.5 million gallons of water were pumped into massive tanks (it took 5 days to fill them!) to film many of the underwater scenes. However, even then filming in a big pool just doesn’t look the same as the ocean. To mitigate this, thousands of small black beads were floated on the surface of the water to control light saturation and reflection. It worked, and the icy blue depths of the ocean were wonderfully recreated.

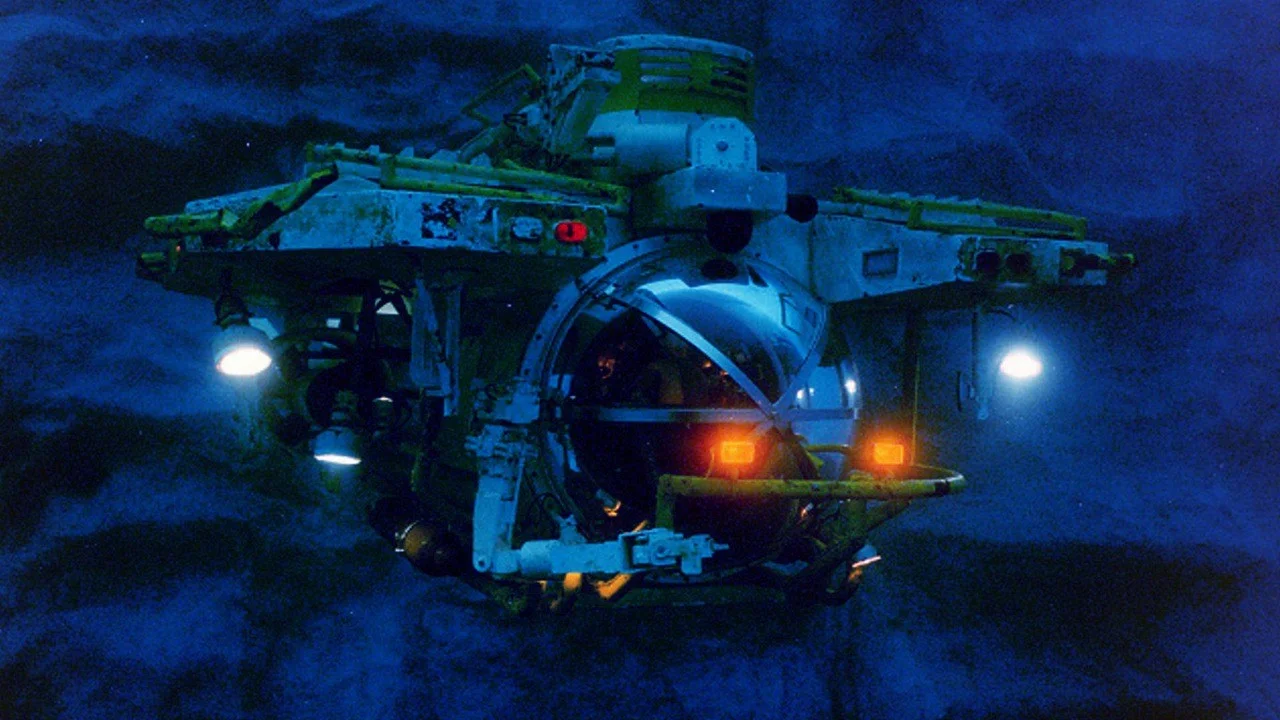

One of the more dramatic set pieces of the film takes place about halfway through when our heroes Virgil (Ed Harris) and Lindsey (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) are in tense and calamitous submersible chase with deranged Navy Seal Lt. Cofey (Michael Biehn). As these two underwater vessels repeatedly smash into each other, one can’t help but notice how visceral it all is, and seemingly expensive it must be to break these massive toys. Well, they weren’t. James Cameron spent much of his career not just as a revered director but as a student of Roger Cormin who was a legend in the field of miniatures in film production. Cameron worked in his studio learning the trade of miniatures and would put it to use in many of his films, proving integral to the chase sequence in the Abyss. These miniatures were about a quarter of the size, but with the light and electrical rigs still weighing in around 450 pounds. They were RC controlled with divers underwater with the control decks to see what they were doing. Any outward shot of the crafts that didn’t’ involve a shot of the characters were usually accomplished this way. It was a traditional method then, anachronistic by todays standards, but it still looks great.

The method and visual story boarding of one of the subs, fractured and leaking, dramatically collapsing into itself after succumbing to intense pressure was even more challenging. The cinematic framing and just outside of mid range shot- coupled it with it being fairly stationary- resulted in them using an actual submersible dome, not one of the miniatures. However, those domes were too thick and too valuable to be cracked. An alternative approach was needed, one that was a mixture of ingenuity and truly old school methods. The dome was lined with random streaks of sellotape and backlit from inside the dome. The lighting was covered up with a flag that was slowly removed. As the light reached the interior dome, it would blot out the actual tape save for its more defined edges, mimicking the cracks in the glass. Clever!

It being a 30 year old film, not everything has aged so well, and in some parts you can see the visual constructs coming apart at the seams so to speak. In that very same sequence there are plenty of shots where you do see the actors in their submersibles. For the close ups inside, it was just a matter of redressing and filming stationary inside of old repurposed pods. But Cameron also wanted shots of his actors up front from the outside of the vessels with a view of the action in the water. This proved a bit more unattainable. To achieve this, they used rear projection- it didn’t look great than and it looks comically hideous now. Basically the crew would film scenes else where and that footage would be played on a small back lit projector screen rigged up inside the mini pods. Cameron loved using this trick back in the 80s and 90s. Many of the driving shots in T2 use this method, and when Ripley and the marines run for their lives in Aliens from the crashing and fiery wreckage of the doomed Evac ship, that’s all rear projection. The problem in The Abyss was, to make the projector screens visually perceptible in the water, they had turn the brightness all the way up. Furthermore, we had actual sized actors compressed into screens meant to fit into subs that were 25% scale. The result was deformed and overly salient visuals of the pilots amidst the subdued and delphic blues of the rest of the shots. They were compositional messes, but that’s 80s sci fi for you.

Some of the more ambitious asks from Cameron regarding the aliens were also just too far beyond the reach of practice effects, at least looking back on it 30 years later. Much of the climax of the film offers full and unobstructed view of the aliens and their massive aquatic vessel. As Virgil is whisked through the labyrinthine tunnels of the ship, The Abyss takes on a strange Flight of the Navigator aesthetic. For the aliens themselves Cameron told visual effects supervisor Steve Johnson he wanted creatures that were heavenly and weightless. They needed to be see through and emit light from within, and no discernable moving parts. Johnson went with silicone constructs that had fiber optic lighting embedded throughout. Unfortunately, the movements were always stilted and awkward as oppose to an ethereal naturalness that Cameron was looking for. The mixture of filming underwater and lighting something that was its own internal flashlight made for something that worked in small doses in the first two acts of the film, but was visually out of synch towards the end of the third act when they are predominant.

Of course, This is The Abyss we are talking about here. No one really remembers the histrionics of the submersible chase sequences or the alien mother ship. The main reason we are here is of course the pseudopod. A barely one minute long sequence but one that revolutionized visual effects for all movies that followed. In the scene our crew is stunned to observe that the aliens can manipulate the properties of water to such an extent that they form a wandering water tentacle. As this tendril of water, navigating the terrestrial confines of the oil rig, meets our characters, it mimics their likeliness by grafting the form of a human face onto its end. While evidently simple enough in the year 2019, the ambition behind such an idea in 1989 cannot be overstated. Cameron and his team were not even sure technology for the shot existed. So he turned to the best of the best- Industrial Light and Magic- to see if it could be done. To begin, ILM started modeling still images based on storyboards on a prototype software that would become known as Photoshop. Once they had a 3D model in software they considered everything from stop motion to claymation to render it. In the end, ILM created custom computer animated imaging software to create the pseudopod.

The procedure was so experimental at that point that Cameron wrote the pseudopod scene in such a manner that nothing narratively or expositionally important happened, thus insuring that if things went sideways he could ditch the scene all together and the film would still make sense. When ILM showed him their progress, everyone on the crew was blown away and what could have been relegated to dropped story board ideas became the visual centerpiece of the film. This is the tech that gave us the T1000 in Terminator 2. This is the moment that proved that CGI could be a viable means for visual effects in films. Indeed, it became the visual future of the medium. Every time you see Thanos throw a moon at Iron Man, or spend an hour and half immersed in a Pixar film, take a moment to remember the origin of all of it was birthed in the murky waters of The Abyss. That being said, It’s the film’s commitment to practical effects and that commitment from all subsequent directors that heeded its call that ensures the wonders of CGI stay wondrous and not an overwrought saturation of fakery.