In Mad Max: Fury Road, Immortan Joe's Vile Cowardice Is The Perfect Foil To Furiosa's Heroism

“You are relying on the generosity of a very bad man”

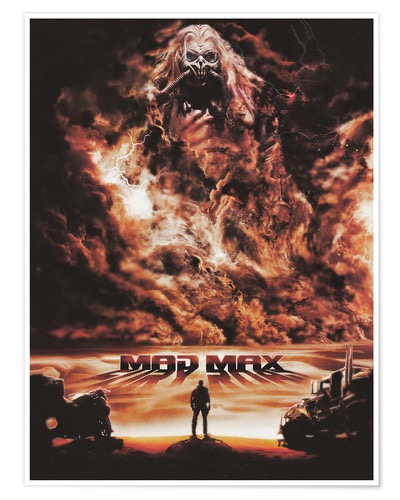

art work by Barrett Biggers via posterlounge

Tristan Young @talltristan

Just a few short years ago it seemed unthinkable- laughable even- that a Mad Max film could inspire thoughtful and provocative think pieces on the most urgent socio-political issues of our time. These were the weird post apocalyptic B movies with tonally bizarre compositions and occasionally Tina Turner in a place called Thunderdome. The 2015 release Mad Max: Fury Road resoundingly changed all of that. It’s long and problematic inception and gestation yielded little more than stultifying shrugs as its release became a firm possibility. After it came out however, it was immediately hailed as not only one of the seminal action films of a generation, but so much more than that. Beyond its hyper stylized and astoundingly gorgeous color grading, beneath its ostensibly simple story as articulated through one improbably perpetual car chase, were fiercely rendered themes of personal agency, feminist optimism, and environmental calamity. The film succeeds not only by casting this rhetoric in the light of capable and sympathetic characters, but also showcasing its antithesis through one of the biggest assholes in recent film canon- Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne). What a jerk. Beyond being a tyrannical despot, his actions are more subtly malignant than first viewing may imply, and is an integral foil to articulate why, yes, it is exactly Furiosa’s (Charlize Theron) viewpoint that needs to become the future of what’s left of the planet.

As our film opens, Mad Max leans heavily into world building mostly through proto nation state alliances and fascist control, both being facilitated by squeezing an already anemic resource based economy. The tyrant Immortan Joe rules the comparatively speaking idyllic Citadel. Idyllic in the sense that it seems to be the one place where plant life can grow and water is at least somewhat available- albeit dolled out in a manner that is both third world and Orwellian at the same time. Immortan Joe controls all access to water, vegetation, and to healthy females deemed suitable for reproduction. In all cases, access is restricted. Beyond the Citadel is Gastown, which appears to be the key producer of fuel- ‘guzzleine’ as they call it- the main resource which makes the dust bowl of a world function. A bit further off is the Bullet Farm where- well you get the idea. The respective rulers of these settlements maintain their power through expectedly brutal and totalitarian means.

Immortan Joe takes things several steps further, using particularly insidious means to assert his authority over his Citadel. Beyond being a scary and jingoistic war lord, he has cultivated a Stalin-esque cult of personality around himself. He achieves this through propagating ritualistic and cult like behavior amongst his followers that is geared less towards shared mythos and iconography and more towards stunting their mental growth. In doing so he subjugates his people on an intellectual level, attacking their means of critical thinking and inflating their juvenile dependency. His vicious army of followers, his War Boys, are not just a symbol of Joe’s might but of their own suffering.

Some of the most visual spectacular moments of Mad Max occur when Joe’s War Boys, emboldened with psychotic energy and commitment to their cause kamikaze themselves upon rival vehicles. Before they erupt in an immolating explosion of their own making, they spray what looks like silver spray paint over their mouths. One will not suicide themselves before doing so, and also screaming to their brethren, “Witness Me”. Only when they are shiny and chrome, as they put it, and positive that others are there to view their heroic and destructive deed, are they convinced a path to the afterlife, to Valhalla, will be open to them. These ideas of being witnessed being requisite to get into their version of heaven, are childish. It is the equivalent of an adolescent making sure all his pals are watching before he pulls a sick jump off the ramp with his bike. This is exactly how Joe wants it. He wants his warriors in a state of arrested development. The destructive capabilities of a full grown person, but the logic and common sense of a child. This will ensure obedience and deter resistance to his authoritarian will.

Joe spreads these tales of religious patronage in the form of the shiny chrome spray paint for other reasons. Writer/Director George Miller has gone on record stating its not just a ritualistic action, the spray paint. The substance is also mixed with a powerful narcotic meant to stimulate ferocious commitment to the task at hand- to Joe’s brutal regime. Evidence exists elsewhere throughout the film of how Joe inters his people into this reduced mental capacity. The young toddlers are raised and dressed as their adult War Boy counterparts to ensure indoctrination at an early age. Even the baddest, scariest grunt in Joe’s entourage calls him daddy and speaks in particularly child like terms upon learning that he –briefly- had a baby brother. These hard killers all sound like kids. Kids often don’t question daddy’s intentions.

Furiosa did, and compelled Joe’s prized breeding wives to to the same. The sharp contrast between females rising up against a bunch of violent and pugnacious dudes has obvious feminist connotations. Indeed, it’s that message that is the most vital and successful one of Mad Max. However, in addition to that it also draws a line between critical thinking and indoctrination. The moment we meet a character like Furiosa, and learn more about what makes Max (Tom Hardy) tick, we see how much more characters that can make their own decisions are capable of in this world. It also reveals the fallacy and fragility of Joe’s rule. The moment you introduce actual adults into the mix Joe becomes swamped with an increasing number of enemies and deserters, from War Boy Nux (Nicholas Hoult) to Furiosa’s matriarchal sisters. Whereas Joe’s War Boys, with their myopic outlook, seem designed to ensure conflict in perpetuity, the plot moves forward as common sense is introduced into the system. Furiosa’s logical observation, “You are relying on the generosity of a very bad man”, is what compels Max to ally with her over returning the wives to Joe. It’s Max shrinking from the glory of heroic victory, as the War Boys are conditioned to idolize, when he acknowledges he’s just not good enough with a sniper rifle to take the shot. Instead he cedes to the final shot to fend off the incoming Bullet Farmers to Furiosa, someone he knows has a better chance than him of pulling it off. Time and time again, it’s assessing a situation and making the best choice based on what one can observe that keeps our heroes alive. This is something Joe has gone to lengths to prevent his people from being capable of.

This pernicious influence extends into the environmental lens of the film, and again it is contrasted through the more thoughtful and measured influence of Furiosa. As Joe greedily hordes the well spring of water underneath the Citadel to himself, he occasionally offers a scant amount to his destitute people. As he does so he ominously warns, “Do not become addicted to water”. He treats a necessity of life like a narcotic, while literally encouraging his armies to dose themselves with psychotropic substances. He keeps the water to himself while building a new world infrastructure on, of all things, fucking oil; exactly the substance and industry that has put our actual world in the precarious condition it is in. As we wonder if our grandchildren will be the last generation on earth that can live a life in any way recognizable to our own, there is something particularly nefarious about Joe extolling the virtues of oil while spreading propaganda about water leading to toxic dependency.

As real life world leaders expend as much energy and capital they can to do as little possible about the defining threat of our existence, we watch a hypothetical future in which hyperbolic versions of the same leaders have learned no real lessons. The world can literally burn and these men will gladly do it all over again so long as they stay on top. This is an abdication not just of morality but also responsibility; that the transactional industries of The Citadel, Gastown, and Bullet Farm are really just zombified versions of the zero sum economics that could very well choke out our planet. There is something especially frustrating about seeing a post apocalyptic world in which it’s still these dick bags are the ones who are in power.

In an interesting structural nod to the road trip nature of the film, the further we move from Joe’s regional power, the more his bull shit becomes apparent. As our characters try to put more and more distance between them and the Citadel, it’s Furiosa- not Joe- who becomes the means of guidance and wisdom. Not just to the wives, but to Max and Nux. As he spends more time with Furiosa, the apathetic and vagabond Max becomes more responsive to the ideas of goals larger than himself, and redemption. Not personal redemption however. He and Furiosa both speak of this, yet Furiosa is depicted as an altruistic person. And while the Mad Max films always depicts him as a bit of a shit kicker, Max always sides with the good guys. The redemption Max learns from Furiosa is one of the entire species, to try and set things right. As Nux is exposed to view points beyond that cultish War Boys he has more and more trouble defending the actions of his people. Perhaps the most central line of the entire film is when Nux struggles to explain that the sorry state off affairs they are all in is not Joe’s fault; “Then who killed the world!?” the wives furiously respond. These are questions Joe doesn’t want his people to ask, but Furiosa inspires those around her not to except things for the way they are. If Joe is stagnation, Furiosa is growth, in terms of personhood, maturity, and even on a larger scale. Small men like Joe won’t last in the world she symbolizes.

Joe likely knows this, and that’s in part what makes him a great villain. He really doesn’t do much more than drive around and look nightmarishly scary. But his commitment to poisoning the minds of his people and the world itself just to stay on top his perch is an excellent antithesis to the hardened and selfless virtue of Furiosa. She is one of the best heroes of the last decade, but every great hero needs a great villain. Instead of a truly formidable counterpart, Mad Max made the toxic and calamitous realties of our world her enemy. What better way to render those realties than through a malicious and deformed bastard reliant on the suffering of others? Consider that the next time you are oddly, and unnervingly satisfied when Furiosa rips his face off.